1. Introduction

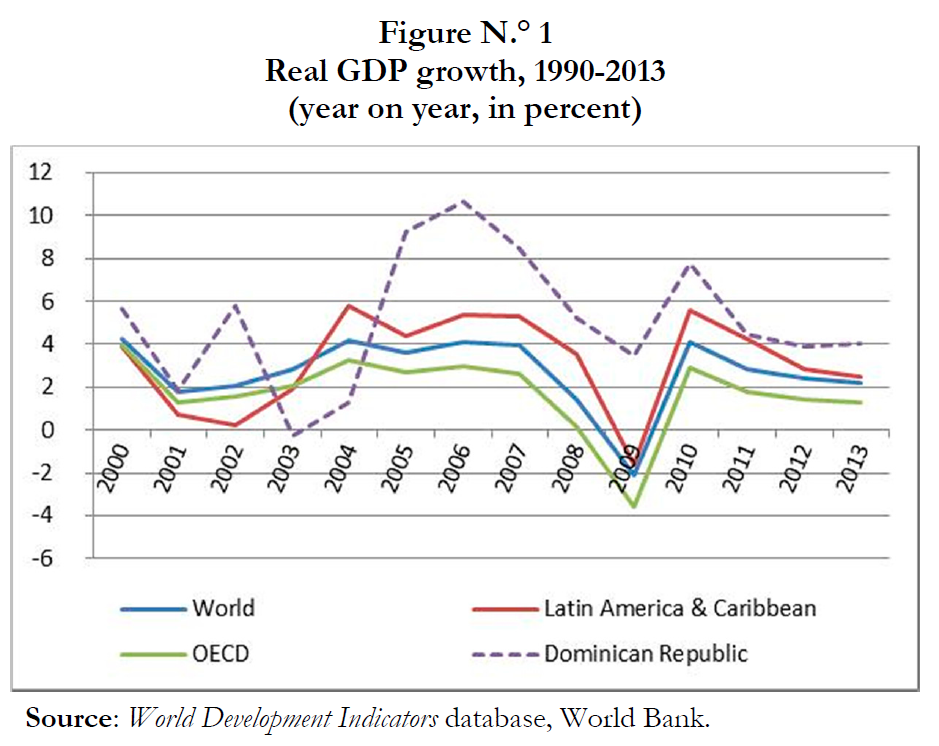

The world economy continues to recover from the recession that followed the global crisis of 2007/08, albeit still slowly and unevenly across regions and economic areas by comparison with previous upturns. Activity slowed gradually after 2010, as the effects of stimulus packages that were put in place in the immediate aftermath of the crisis waned (Figure 1), although it gathered momentum in 2014 on the back of some renewed dynamism in the advanced economies, and despite a slowdown in the emerging-market and developing economies. In the advanced economies, activity is poised to gather steam in the course of 2015 and over the medium term on the back of supportive monetary conditions, a slower pace of fiscal consolidation, continued financial sector repair and lower oil prices. The emerging-market economies have been driving growth since the onset of the global crisis, although they have lost impetus since 2010. As for Latin America and the Caribbean, lower commodity prices, a slowdown in exports on the back of a less buoyant expansion in China and other importing markets, and falling appetite for risk in expectation of monetary normalization in the advanced economies will weigh on the region's near-term growth.

Although the outlook is improving for the global economy, raising investment and productivity remains a common challenge for both advanced and emerging-market economies alike. In the advanced economies, structural reforms to remove regulatory impediments to competition in product markets and efforts to make labour markets more dynamic will be essential for unlocking opportunities for growth and job creation. Income inequalities have also widened in most advanced economies, which is sapping confidence in governments and institutions. In the case of Latin America and the Caribbean, prospects for growth over the longer term need to be interpreted against a background of structural transformation that will have to be pursued to put the region’s economies on a path of stronger, more inclusive growth. Improving educational outcomes and the business environment, tackling institutional weaknesses that hold back investment, and addressing poverty and high income inequality are among the continent’s main challenges.

To set the scene for more specific discussions on the prospects for the Dominican Republic’s economy throughout this volume, this short paper will present the outlook for the global economy and its implications for Latin America and the Caribbean. It will also lay out a few longer-term, structural challenges that are common to most economies in the continent and that will need to be addressed in the years to come in support of stronger performance. Due to space limitations, the analysis of these specific challenges will not be exhaustive and should be interpreted as a broad-brush assessment of the reform areas that could feature prominently in the policy agenda for the continent.

2. Near-term prospects for the global economy

Recovery from the global crisis has been particularly hesitant and uneven in the advanced economies and will likely continue at a rising but still subdued pace over the neat term.1 While the world economy is expected by the OECD to grow by about 3.2 percent in 2015 (on a purchasing power parity basis) and just short of 4 percent in 2016, growth is poised to be much lower in the advanced economies, at close to 2 percent in 2015 and 2.5 percent next year. While activity has picked up in earnest in the United States and the United Kingdom, the recovery has been much slower in the euro area and Japan. In general, macroeconomic policies have been supportive, including the monetary stance, which has facilitated financial sector repair and deleveraging. Growth has been buttressed by a slower pace of fiscal consolidation following a period of substantial retrenchment, especially in those countries that experience a sharp deterioration in their public finances after the crisis.2

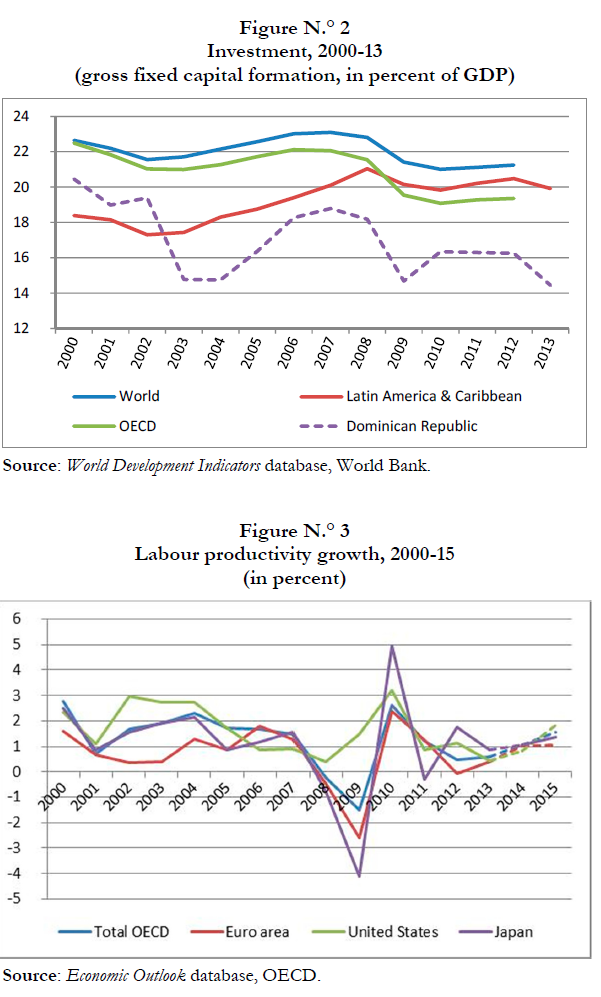

Looking ahead, weak investment demand and slow productivity growth will bear down on the recovery (Figures 2 and 3). Labour market conditions will likely continue to improve in tandem with the pickup in activity in the advanced economies, although unemployment remains high in many countries, especially in Europe. Policy normalization will shape the recovery over the near term, with the pace of withdrawal of monetary stimulus depending on the conditions in individual countries and economic areas, starting with the United States, where slack is disappearing and inflation is moving towards the target. Differential monetary policy stances in the advanced economies will lead to exchange rate movements that will shape the prospects for inflation and financial market conditions. As for fiscal policy, the main challenge will be to balance still needed support for growth within the fiscal space available in individual countries with efforts to ensure sustainability in the public finances over the long term.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, the recovery is set to be gradual and to a large extent conditioned by policy normalization in the advanced economies. According to the IMF, real GDP growth weakened to about 1.3 percent in 2014 and will likely slow further in 2015 before gathering momentum throughout next year. The weakness in commodity prices, including oil, following years of sustained gains, will continue to weigh on growth in the natural resource-based economies in the region, especially in South America, through losses in export and fiscal revenue, as well as leading to currency weaknesses. Sentiment has deteriorated in general, taking its toll on investment demand. By contrast, the recovery in the United States will support a pickup in activity in Central America and the Caribbean, despite competitiveness gaps, weaknesses in the public finances and financial sector fragilities in some countries. Growth is expected to remain robust in the Dominican Republic, following strong performance in 2014.

Policy responses will need to adjust domestic absorption to the tighter external environment while allowing for some countercyclicality where needed and fundamentals are strong. A prudent macroeconomic stance will be required to guard against the risks associated with a reversal in financial market conditions that could arise from the impending monetary normalization in the United States. Exchange rate flexibility will play an important role in this process, so long as inflation expectations are well anchored and fiscal positions are robust. 3

3. Longer-term prospects and structural reform challenges

Structural reforms will need to continue across a variety of policy domains to allow for a faster pickup in investment and productivity in the advanced economies. Labour productivity has been growing at less than 0.7 percent per year on average in OECD countries since 2011, essentially on the back of weak investment. Population ageing will also continue to act as a drag on potential growth through lower labour supply, calling for reforms to strengthen incentives for participation in the labour force by underrepresented groups, including women and older workers. The pace of structural reform has slowed over the recent past, in particular in the area of product market regulation, although progress has been comparatively stronger in the Southern European countries facing fiscal and financial duress.4 This trend will need to be reversed to deliver sustained gains in productivity, as well as encouraging investment and job creation.

Over the longer term, growth prospects in Latin America and the Caribbean will also depend on how fast productivity can be raised across the continent. Lower labour productivity, rather than labour force participation, explains much of the gap in relative income per capita between the countries in the region and the average of OECD countries. The key challenge to this end is to improve educational attainment and outcomes, given the comparatively poor performance of students across the continent on the basis of international standardized tests, such as the OECD PISA.5 Progress in this area would be beneficial on many fronts. It would pave the way for raising the value added of the region’s exports, building on its comparative advantages in resource intensive sectors, as well as contributing to deliver sustained reductions in poverty and improvements in the distribution of income.

Structural reform priorities vary among countries, and in general they go far beyond education and skills. Efforts to improve the rule of law and tackle corruption would contribute to raising potential growth by improving the business environment, a task that also depends on further pro-competition reforms in product markets. Moreover, progress is needed to modernize tax systems and improve domestic revenue mobilization, given the region’s low tax collection in relation to GDP, as well as enhancing the cost effectiveness of government programmes. This will be essential for governments to provide quality services, especially in education and health care; finance needed investment, especially in infrastructure, and respond to the broader needs and aspirations of society.

Notas

- See OECD (2015) and IMF (2015) for detailed projections and discussions on the outlook and associated policy drivers and risks.

- Much has been said about the effects of fiscal policy on activity in the advanced economies since the crisis, and a rich body of empirical work has emerged on the effectiveness of fiscal policy in an environment of ultra low interest rates. See de Mello (2013a) for a review of the literature and discussion on the estimation of fiscal multipliers for the advanced economies.

- See de Mello and Moccero (2010) for empirical evidence on the role of monetary policy in macroeconomic stabilization in selected Latin American countries.

- See OECD (2014a) for a overview of pro-growth structural reform requirements and follow-through in OECD and selected partner countries.

- See OECD (2014b) for a comparison of scores among the PISA participating coun tries. See also de Mello (2013b) for a more detailed discussion for the case of Brazil.

4. References

International Monetary Fund. (2015). World Economic Outlook. Washington, D. C.: The Author.

Mello, L., De. & Moccero, D. (2010). Monetary Policy and Macroeconomic Stabilization in Latin America: The Cases of Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico. Journal of International Money and Finance, 30, 229-245.

Mello, L., De. (2013a). What Can Fiscal Policy Do in the Current Recession? A Review of Recent Literature and Policy Options. Hacienda Pública Española (Review of Public Economics), 204, 113-39.

Mello, L., De. (2013b). “Brazil’s Growth Performance: Achievements and Prospects”, in Augustin K. Fosu (Ed.), Achieving Development Success (pp. 295-320). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos.(2014a). Going for Growth. Paris: El autor.

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos. (2014b). Education at a Glance. Paris: El autor.

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos. (2015), OECD Economic Outlook. Paris: El autor.

Datos de filiación

Luiz de Mello. He is Deputy Director of the Public Governance and Territorial Development Directorate at the OECD. Previously, he served as Deputy Chief of Staff of the OECD Secretary-General. He started his career at the OECD in the Economics Department, where he was the Head of Desk responsible for bilateral surveillance activities with Brazil, Chile and Indonesia before becoming the Economic Counsellor to the Chief Economist.

Prior to joining the OECD, Mr. de Mello worked in the Fiscal Affairs Department of the International Monetary Fund, where he was involved in different projects in the areas of public finances, as well as programmer monitoring and policy surveillance, with an emphasis on emerging-market and transition economies in Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe.

Mr. de Mello holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Kent, United Kingdom, where he started his career as a lecturer. His main areas of interest are open-economy macroeconomics, public finances, and growth and development issues.