Ciencia y Salud, Vol. VI, No. 2, mayo-agosto, 2022 • ISSN (impreso): 2613-8816 • ISSN (en línea): 2613-8824 • Sitio web: https://revistas.intec.edu.do/

TRAVEL MEDICINE IN THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

La Medicina del Viajero en República Dominicana

Cómo citar: Castillo Santana E, Arámboles YDJ, Catoia Varela M, Bautista Branagan CE, Lara Reyes EM, Días da Costa M. Travel Medicine in the Dominican Republic. cysa [Internet]. [citado 17 de mayo de 2022];6(2):17-21. Disponible en: https://revistas.intec.edu.do/index.php/cisa/article/view/2505

Introduction

Travel Medicine is an interdisciplinary specialty that deals not only with the prevention of infectious diseases during travel, but also with personal safety and the prevention of environmental risks in national and international destinations.1 The increase in the number of travelers, the diversity of both their itineraries, and the activities carried out during the trips are just some of the factors that contributed to the birth of this specialty.2 Furthermore, travelers can import diseases to their places of origin, which can be spread such as COVID-19, yellow fever, measles, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and others.

The Travel Medicine specialty has existed for more than 30 years, despite the existence of regional and world scientific societies such as the Latin American Society of Travel Medicine (SLAMVI)3 and the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM)4 dedicated to the diffusion of this specialty, the knowledge about this area by Dominicans is very precarious. In the context of the COVID-19, Travel Medicine receives a special highlight, many people who, before the pandemic, did not imagine the health risks that a certain trip could represent, now thinks differently.

Material and methods

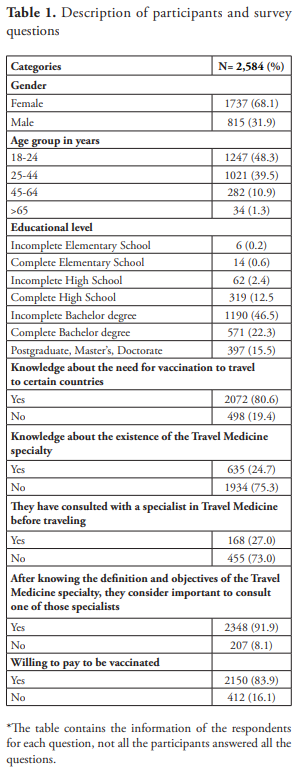

We conducted a virtual survey of eight multiple choice questions, through Whatsapp, Facebook and Instagram, from November 20 to December 20, 2020, convenience sampling. This study is part of an investigation carried out in nine Latin American countries, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Instituto Nacional de Infectología Evandro Chagas, Fiocruz. Study data and data gathering form links were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools from that same institution.5, 6 After reading and signing the electronic informed consent, 2,584 Dominicans aged 18 or older participated in the study. The average time to complete the form was one minute. The first three questions were about demographic data (gender, age and level of education), then five specific questions to assess the knowledge of Dominicans about Travel Medicine. We analyzed the distribution of responses across the entire dataset, summarizing categorical variables such as counts and percentages, using R software.7

Results

Of the 2,584 participants, 1,737 (68.1%) were women, 1,247 (48.3%) were between 18 and 24 years old, and 1,190 (46.5%) had incomplete university education. Only 635 (24.7%) of those surveyed knew the specialty of Travel Medicine and 168 (27.0%) had made a pre-trip medical consultation. Concerning the knowledge about pre-travel vaccination, 8,447 (90.0%) of the surveyed gave a positive answer. After knowing the definition and objectives of this specialty, 2348 (91.9%) participants consider it important to carry out a pre-travel consultation with a specialist. Other characteristics of the population and a summary of the responses to the survey questions are listed in Table 1.

Discussion

The Dominican Republic is the Caribbean country with the most reported cases of COVID-19,8 which translates into a differentiated perception of the disease and the need for measures to control it. The perception of many Dominicans in relation to vaccination changed due to the experience of the pandemic. The main reason was seeing a loved one suffering from severe COVID-19 or dying from this disease.9 It is to be expected that the pandemic will also influence the way Dominicans prepare for future trips. As well as in the way of thinking in relation to the risks to individual and public health that these may represent. The pandemic taught us that humans are also vectors, we can transport infectious agents from one country to another, a situation that, depending on various factors, can result in a global public health crisis, such as COVID -19.

Pre-travel vaccination is one of the pillars of Travel Medicine. Several of the vaccines that exist for the protection of travelers are not part of the vaccination schedule of the Programa Ampliado de Inmunizaciones (PAI) of Dominican Republic, but are available in private vaccination centers. 2,150 (83.9%) of those surveyed are willing to pay to be vaccinated, which suggests that despite the fact that vaccination is not available in public health services and they are not in the habit of consulting prior to travel, Dominicans are willing to adopt the necessary preventive measures to reduce the risk of getting sick as a result of a certain trip, and thus avoid the spread of infectious diseases when returning to the country.

It is important to note that not only Dominicans who travel abroad are at risk, the millions of foreigners who arrive in the Dominican Republic each year are also at risk of transmitting infectious diseases, as occurred with the introduction of COVID-19 in our country. , and to catch diseases such as Dengue, Diphtheria and Malaria,10 diseases that were reported in the Dominican Republic in 2020. Highlighting the Diphtheria outbreak that our country faced in the first quarter of 2021.11 There are no vaccines for some diseases, such as Malaria, but there are other strategies that can be applied to reduce the risk of contagion, such as prophylaxis with drugs, use of repellent, among others.12 All the preventive measures explained to patients in the pre-trip consultation, together with the post-trip consultation in which both travelers who return healthy, as well as those who return with diseases acquired during the trip are treated and accompanied, guarantee the preservation of the health of travelers before, during and after traveling.13

The specialty is not only dedicated to the prevention of infectious diseases, but also educates travelers regarding behaviors, personal safety and cultural realities that they should know before reaching their destination. An example of this is the counseling that homosexual travelers receive, since in certain countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Syria there is the death penalty for gays, which makes them places of high risk for these travelers.14 Another important element is the adaptation to altitude, due to the variation between the different countries of the world, such as La Rinconada (Peru, 5,100 meters), Tuiwa (China, 5,070 m) among others.15

In the Dominican Republic, Traveler’s Medicine is practically non-existent. Our country does not appear on the list of countries registered with the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM) that offer this service.16 The COVID-19 pandemic can mark a before and after in this specialty in the Dominican Republic, all It will depend on how the health authorities and health professionals handle the situation in favor of promoting Traveler’s Medicine in the Dominican Republic.

Conclusion

The lack of knowledge of the specialty and the lack of professionals who provide this service are the main barriers for Dominicans to access the Traveler’s Medicine consultation. It is necessary that the competent authorities, using scientific evidence and taking as an example the global spread of COVID-19 through travelers, make the population aware of the importance of pre- and post-travel medical consultation, as well as the creation of this service in Dominican public hospitals.

Authors’ Contributions

ECS and MDC conceived and designed the proposal; YJA, CBB and ELR collected the data; MCV processed and analyzed the data; ECS drafted the manuscript; MDC reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interests Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Referencias

- Hill et al. The Practice of Travel Medicine: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 2006:43. [Online]. Disponible en: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/43/12/1499/277259?login=true [Acceso 17 de febrero de 2021].

- Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE et al. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. New Engl J Med 2006; 354:119–30. [Online]. Disponible en: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa051331 [Acceso 17 de febrero de 2021].

- Sociedad Latinoamericana de Medicina del Viajero. SLAMVI. Recomendaciones para via- jeros. [Online]. Disponible en: https://cabd4a59-051e-4cac-99bd-20b5aa3f3281.filesusr.com/ugd/eb4674_9fd5062be4264336aebe40e623c7082e.pdf [Acceso 25 de abril de 2021].

- International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM). [Online]. Disponible en: https://www.istm.org/[Acceso 25 de abril de 2021].

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support, J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):377-81. [Online] Disponible en: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1532046408001226 [Acceso 6 de febrero de 2021].

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L et al. REDCap Consortium: Building an international community of software partners, J Biomed Inform. 2019 May 9. [Online] Disponible en: https://do.trabajo.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [Acceso 6 de febrero de 2021].

- R Core Team (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Online] Disponible en: http://www.R-project.org/ [Acceso 6 de febrero de 2021].

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. COVID-19 dashboard. [Online]. Disponible en: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (2021). [Acceso 25 de abril de 2021].

- Castillo E, Catoia M, et al. (2021) Immunization in Latin America in the context of COVID-19: a regional survey. Artículo/Manuscrito entregado para publicación.

- Vigilancia en Salud Pública. Malaria en Repú- blica Dominicana. [Online]. Disponible en: https://temas.sld.cu/vigilanciaensalud/2020/02/12/malaria-en-republica-dominicana-10/ [Acceso 26 de abril de 2021].

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS). Actualización Epidemiológica Difteria en la isla La Española 2 de marzo de 2021. [Online]. Disponible en: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/53380/EpiUpdate2March2021_spa.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y [Acceso 26 de abril de 2021].

- Capdevila J.A, Icart, R. Profilaxis de la malaria en el viajero. Revista Clínica Española, 2010; 210 (2): 77-83. [Online]. Disponible en: https://www.revclinesp.es/es-profilaxis-malaria-el-viajero-articulo-S0014256509000605 [Acceso 26 de abril de 2021].

- Centro Médico Palmares. Medicina del Viajero: Una consulta previa, imprescindible para un viaje seguro. [Online]. Disponible en: https://www.centromedicopalmares.com/medicina-del-viajero-una-consulta-previa-imprescindible-para-un-viaje-seguro/ [Acceso 26 de abril de 2021].

- El Mundo. Los destinos más peligrosos para un viajero gay. [Online]. Disponible en: https://www.elmundo.es/viajes/el-baul/2018/06/28/5b054b4ce5fdeaa5738b4648.html [Acceso 26 de abril de 2021].

- La Vanguardia. Viaje a destinos de alturas; qué hacer y cómo afecta a los niños. [Online]. Disponible en: https://www.lavanguardia.com/ocio/viajes/20200130/473195913683/consejos-viajes-ninos-destinos-altura-travel-kids.html [Acceso 26 de abril de 2021].

- International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM). Online Clinic Directory. [Online]. Disponible en: https://www.istm.org/AF_CstmClinicDirectory.asp [Acceso 25 de abril de 2021].