Ciencia y Salud, Vol. V, No. 3, septiembre-diciembre, 2021 • ISSN (impreso): 2613-8816 • ISSN (en línea): 2613-8824 • Sitio web: https://revistas.intec.edu.do/

MODEL ADHERENCE TO TREATMENT OF DISEASES ACQUIRED BY ASYMMETRIES BETWEEN JOB DEMANDS AND SELF-CONTROL

Modelamiento de la adherencia al tratamiento de las enfermedades adquiridas por asimetrías entre las demandas laborales y el autocontrol

Cómo citar: Guillén JC, Martínez Muñoz E, Espinoza Morales F, Juárez Nájera M, Bermúdez Ruíz G, García Lirios C, Quiroz Campas CY, Quintero Soto ML, Velez-Baez SS, López de Nava-Tapia S. Modelamiento de la adherencia al tratamiento de las enfermedades adquiridas por asimetrías entre las demandas laborales y el autocontrol. cysa [Internet]. 14 de octubre de 2021 [citado 15 de octubre de 2021];5(3):13-6. Disponible en: https://revistas.intec.edu.do/index.php/cisa/article/view/2311

Introduction

The objective of this paper is to specify a model for the study of occupational health with emphasis on the treatment of diseases acquired by excessive labor demands and reduced self-control of workers1.

Psychological studies of occupational health warn; a) the preponderance of the Demand, Control and Social Support Model (MDCS) and Effort-Reward (MDER) Model; b) the prevalence of stress when there are asymmetries between demands and self-control, as well as imbalance between efforts and rewards; c) once the worker has acquired an illness due to work stress, adherence to treatment emerges as a factor of quality of life and subjective well-being2.

Occupational health models warn that stress can affect biomedical factors; cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and ischemic heart disease that can lead to musculoskeletal disorders, absenteeism, accidents, conflicts, insomnia, depression and anxiety3.

Both models have shown that occupational health and self-care is determined by the type of employment. An increase in risk factors exacerbates the likelihood of illnesses, accidents or disorders related to work activity4.

However, occupational health studies have focused more on prevention than on the study of adherence to the treatment of diseases, accidents or disorders; since workers can be rehabilitated and become productive again, it is necessary to study the adherence to treatment as a determining factor in the quality of life of workers with some disease, especially in those cases of older adults or terminal phase, imminent loss of limb or even life5.

In this sense, the study of adherence to treatment also involves the investigation of grief factors in the face of an imminent loss of limb or human in organizations that operate with high risk and health effects6.

Models that study grief as an expectation of imminent loss of life, limb or sanity pose phases ranging from denial to acceptance, rehabilitation and reconstruction of the meaning of existence7.

However, adherence to treatment, unlike the process of mourning, implies a hope for the preservation of the quality of life, an expectation of well-being and indicates the restoration of occupational health8.

The study of adherence to treatment is the link between an accident, illness, disorder and the reinsertion of the convalescent in a climate of tasks and relationships established by trust, commitment and satisfaction, as well as dedicated to entrepreneurship, innovation and competitiveness9.

However, adherence to treatment involves an internal negotiation of the employee with respect to the demands that organizations will endorse, involves establishing agreements and responsibilities between workers and leaders is not always feasible in traditional organizational cultures, but in adhocratic organizations10.

Therefore, the present work carried out a documentary study with a selection of indexed sources of Latin American repositories —Dialnet, Latindex, Publindex, Redalyc and Scielo—, considering the key words: model, demands, control, social support, imbalance, effort and reward. Subsequently, the information was processed in matrices of content analysis to extract the explanatory variables of adherence to treatment11.

Finally, the model was specified based on assumptions of trajectories of dependency relationships between the variables12.

The model will allow the empirical contrast of the hypotheses, as well as a new specification of the trajectories of correlations between variables in order to incorporate the findings of the literature and the questions of the state of knowledge13.

Model of Demands, Control and Social Support (MDCS)

Occupational health studies have focused their interest on the relationship between organization and worker based on the asymmetries between labor demands and subjective capacity control14.

A labor demand refers to tangible and intangible opportunities of organizational development that materialize in capacity requirements for managers and subordinates, leaders and talents in an organization, but when a function is not visible, the demand encourages the conflict of relationships and causes disinterest, frustration, exhaustion, depersonalization or negligence15.

Demands can be inferred from attitudes toward work as significant differences between managers and subordinates with respect to task climate and adaptation to change, but not with respect to transformational leadership —Motivation to change beyond the labor interest— where the idealization of the leader generates greater inspiration and satisfaction16.

In the case of the balance between efforts and rewards, the idealization of the leader determined a greater effort (β = 0.76), the same that included satisfaction (β = 0.45) and inspiration (β = 0.50) and the effectiveness of the task (β = 0.39) 17.

Even though the transformational leadership style affects satisfaction through transparency and optimism, it is commitment —an indicator of self-control— that increases the quality of performance18.

Therefore, the labor demand, even though it is transferred by a leader that can be transformational and influences the followers, is generated by the degree of commitment (self-regulated control) by the employee with respect to the idealization of their work, leaders and organization19.

This is because the culture of success of an organization complements the dispositions to happiness and satisfaction, as well as the discursive and communicative skills of employees20.

The MDCS warns that the organization can motivate the employee through a climate of trusting relationships and a climate of innovative tasks, but it is the employee’s work history that will determine their degree of self-control reflected in their commitment and satisfaction with their work environment21.

In this sense, the MDCS does not explain the effect of the work culture on the worker’s performance weighted in their degree of effort and commitment22.

Unbalance, Effort and Reward Model (MDER)

Unlike the MDCS that emphasizes the importance of regulating demands and encouraging personal control, the MDER maintains that it is the reward that, in correspondence with the effort, will generate a climate of transparent and trusting relationships, encouraging the climate of tasks and reducing conflicts to its minimum expression23.

It is possible to observe that in the MDCS the increased demand affects self-control, and such asymmetry favors diseases, accidents, conflicts and disorders that the MDER aims to solve with incentive rewards of more effort because it assumes a constant increase in demands24.

However, the studies on stress and burnout warn that these are generated even in work climates of recognition of the effort, since the lack of personal fulfillment is a factor of chronic stress for employees with expectations and capacities to transcend their role, even to the organization itself25.

Emotional exhaustion is not only generated by excessive labor demand, but also by routine or simplicity of the task climate, or by the absence of climates of innovation that demand a creative effort. In addition, being associated with depersonalization, emotional exhaustion is a process that begins with fatigue and culminates with indifference to the workplace. It can even generate frustration, even when the organization encourages their effort26.

Therefore, the culture of success, focused on the innovation of its relationships, processes and products, generates the flexibility, confidence and diversity necessary to reduce stress and burnout, as well as mobbing or any violence and conflict of relationships and tasks27.

Polyvalence –diversity of tasks climates and climate of relationships– associated with exploration (r = 0.91, p <0.001) and innovation (r = 0.71; p <0.001) determines performance (β = 0.61), but a climate of relationships and innovative tasks is generated by the production and socialization of knowledge and the effectiveness of the expected results or the expectations of the established or targets, as well as in the transformational administration (β = 0.38, p = 0.000)28.

Therefore, the quality of performance depends not only on the balance between demands and self-control, or on the balance between efforts and rewards, but also on the avoidance of stress and burnout, as well as on transformational leadership29.

Studies of adherence to treatment in relation to work demands and self-control

This section presents the studies that report correlation or regression coefficients in which the relationship between labor demands and adherence to treatment through self-control is shown30.

These are models in which variables of different order interact, but a linear relationship prevails among the three variables31.

Self-control defined as inconsistency in the intake of medications determined adherence to treatment because they suffered psychological burdens that not only affected their treatment but also influenced the deterioration of their quality of life32.

The determinant of adherence was self-management (β = 0.15, p = 0.002) 33.

That is, organizations that do not monitor the psychological burdens of their employees with high-risk functions and do not promote relationships of collaboration, support and solidarity seem to reduce the management of the health of their employees, guiding them towards the loss of adherence to the treatment of a disease or accident34.

Adherence to treatment determines rehabilitation contrasted a model in which they demonstrated an effect of treatment cost on compliance (B = 0.610, p = 0.0791; OR = 0.54 (0.21 1.40) 35.

This is so because self-management supposes a labor, financial and family support to carry out the fulfillment of the measurement; therefore, the development of human capital is an effective response to the risks and threats of the environment in terms of health, such process is gestated from public investment in academic, professional and employment training and not only as prevention but also as a promotion of risk-free relationships36.

Poor adherence to treatment as a determinant of medication financing, although it prevails that of urban men in compliance with the distinction of other groups37.

That is, adherence to treatment seems to be the result of a patriarchal structure that favors a sector formed as human capital with high self-control compared to other sectors formed as social capital with high solidarity and collaboration38.

The three studies reveal that the structure of public health services, as well as the structure of academic, professional and work training to favor a civil sector determine the adherence to the treatment of diseases and the prevention of risks through the promotion of lifestyles of health free of risks39.

It is a strategy of training policies of self-control in which psychological variables such as beliefs or information processing capacity, information perceptions or biases, knowledge or logics of verifiability and intentions or probabilities of making a decision that will be carried out complement the process of adherence to treatment40.

It is through such a process that the model of demands, control and social support, as well as the model of imbalance, effort and reward, turn out to be palliative institutional strategies in the face of illnesses and accidents41.

That is, the collective self-control of the first model and the personal self-control of the second model turn out to be insufficient to reduce the mediation of a public health system favorable to a sector with high incomes and quality of life estimated in urban services42.

A new model of adherence to treatment based on public management, social and family support in relation to self-control that establishes a balance between the demands of the environment and institutional and personal resources would be supported by prevention strategies for excluded sectors, violated or marginalized and microfinance strategies for peripheral sectors to urban health services43.

The psychological variables of beliefs, dispositions, knowledge and intentions would be influenced by the demands of the environment or risks to health such as the case of diseases and accidents in the occupational field44.

The emergence of a condition not only activates medical consultation or adherence to treatment through the intake of drugs, but also encourages financial and social support strategies that the State could incentive according to the level of development of the community or locality45.

In this way, adherence to treatment would no longer be the result of urban health policies that favor those who have decision-making power centered on their personal and financial resources but would also be the product of policies according to the needs and expectations of communities where prevail the formation of solidarity capital, the climate of support and collaboration to support a disease that is considered shared46.

The state would no longer be only a promoter of self-management and self-control47.

Now a new social function of the State would be in the micro-financing of health services as human settlements move away from urban centrality and other non-favored sectors approach this sub-scheme to deal with their illnesses and accidents48.

Therefore, health services acquire a social feature not only because of the administration scheme but also because of the targeting of needs and supports to marginalized, excluded and violated sectors49.

Specification of the treatment adherence model

The public health models used, the MDCSS and the MDER, can not only be complementary in the prediction of stress, but also relate to the explanation of adherence to treatment for those cases of accidents, diseases, disorders or conflicts arising from the climate of relationships and the climate of tasks that promote trust, commitment, entrepreneurship, innovation and satisfaction50.

The model includes four explanatory hypotheses of the trajectories of correlations between the variables reviewed in the literature51.

The association between demands and social support determines self-control and effort52.

As the worker becomes involved in greater demands for efficiency and effectiveness, the social support of colleagues, friends or family encourages self-control and regulates his effort, but non-recognition will generate stress. In opposite cases, the reward could anticipate adherence to treatment for an illness, disorder, accident or conflict if the worker reaches that stage53.

Unlike the predecessor models, the specified model states that the dependency relationships between the variables not only anticipate stress, but also adherence to treatment54.

The specified model would encourage the follow-up of cases of accidents, illnesses, conflicts and disorders associated with the climate of relationships and the climate of tasks55.

Method

Because the new model assumes the relationship between socioeconomic variables such as per capita income, demographic factors such as gender or age, institutional factors such as micro financing and psychological strategies such as dispositions, knowledge and intentions, it is necessary to carry out an exploratory study of the relationships reported between these variables in order to establish the parameters that indicate probabilities of adherence to treatment or determinant relationships of this variable.

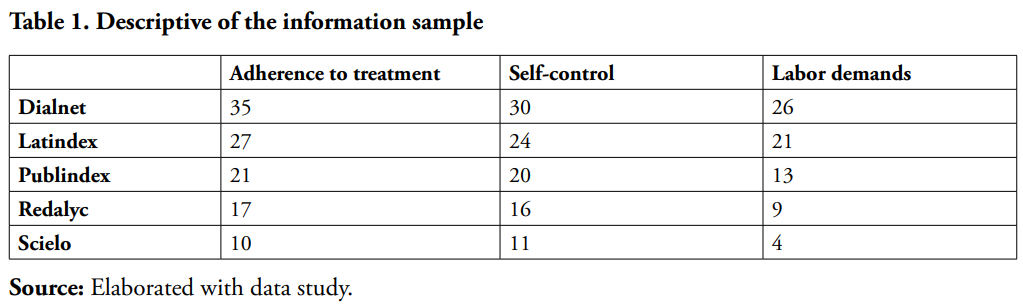

The universe of the data were index repositories such as Copernicus, Dialnet, Latindex, Publindex, Redalyc and Scielo. The sample consisted of the literature selected intentionally, considering the inclusion of the key words of adherence to treatment, self-control and labor demands published from 2005 to 2020 (see Table 1).

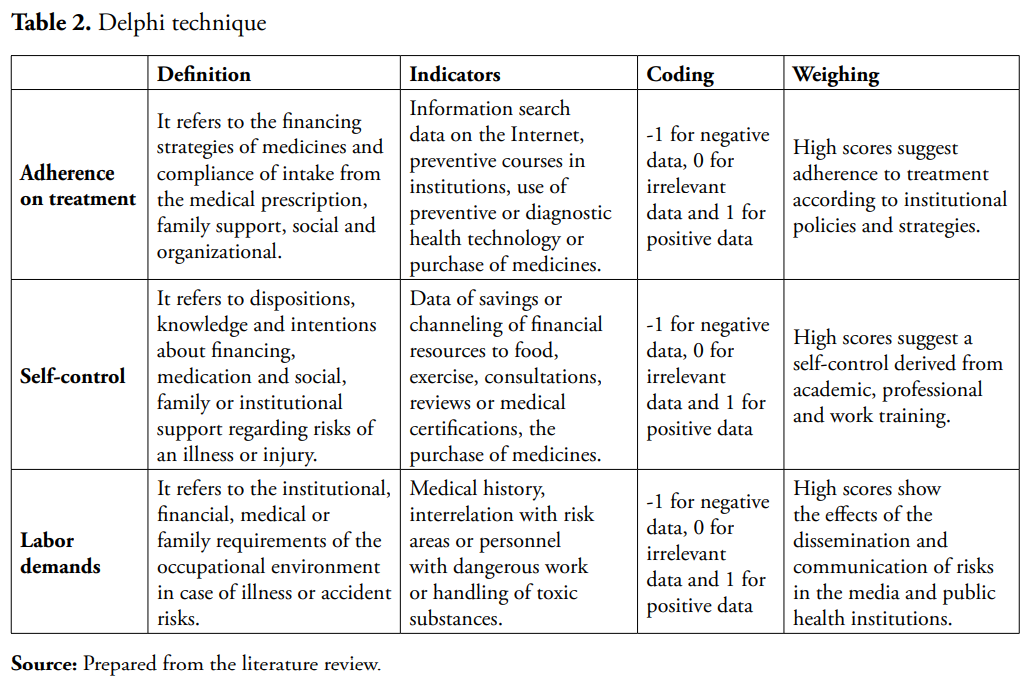

The information was processed following the Delphi technique where pairs of experts in the subject evaluated extracts of the findings reported in the litter with the purpose of establishing the relationship between the variables, considering -1 for negative data, 0 for irrelevant data and 1 for positive data (see Table 2).

In three rounds the experts qualified the extracts. At the first opportunity, they only catered the data, but with some suggestion of registration that was incorporated into the extract in order to be able to qualify it again in a second round56. Once the consensus was established, in the third round the judges compared their first qualification with the second and issued a new qualification in order to reinforce their criteria, or again issue new considerations57.

The information was processed in the qualitative data analysis package version 4.0 in order to be able to quantify distribution parameters and nonparametric relationships58. The chi square was estimated and, based on these findings, an instrument was designed for the validity of the chi and the specification of the model59.

Results

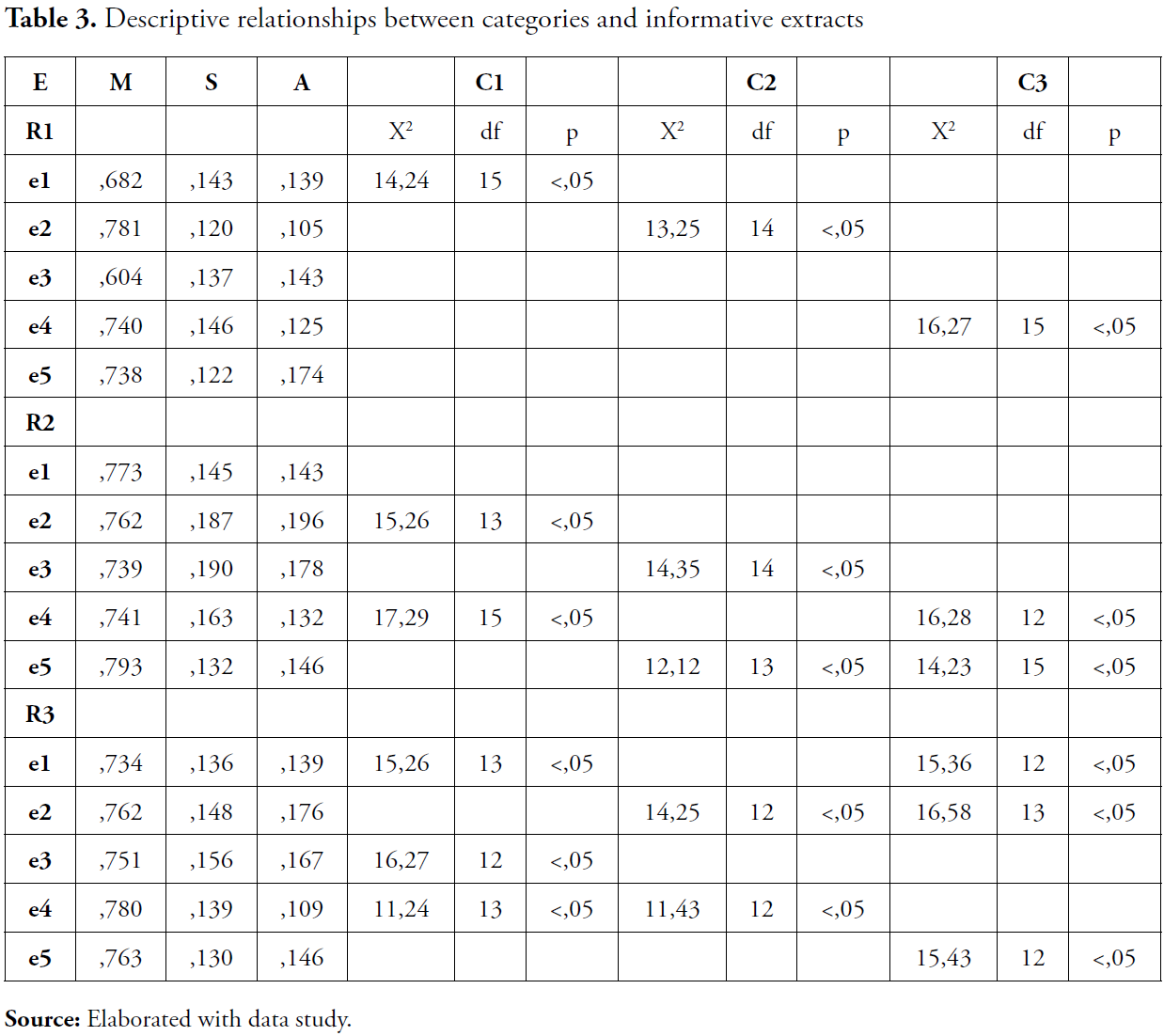

Table 3 shows the relationships between the selected extracts with respect to the three central categories of labor demands, self-control and adherence to treatment. It is possible to observe significant relationships to the extent that qualification rounds succeed one another, as well as a marked consensus in adherence to treatment.

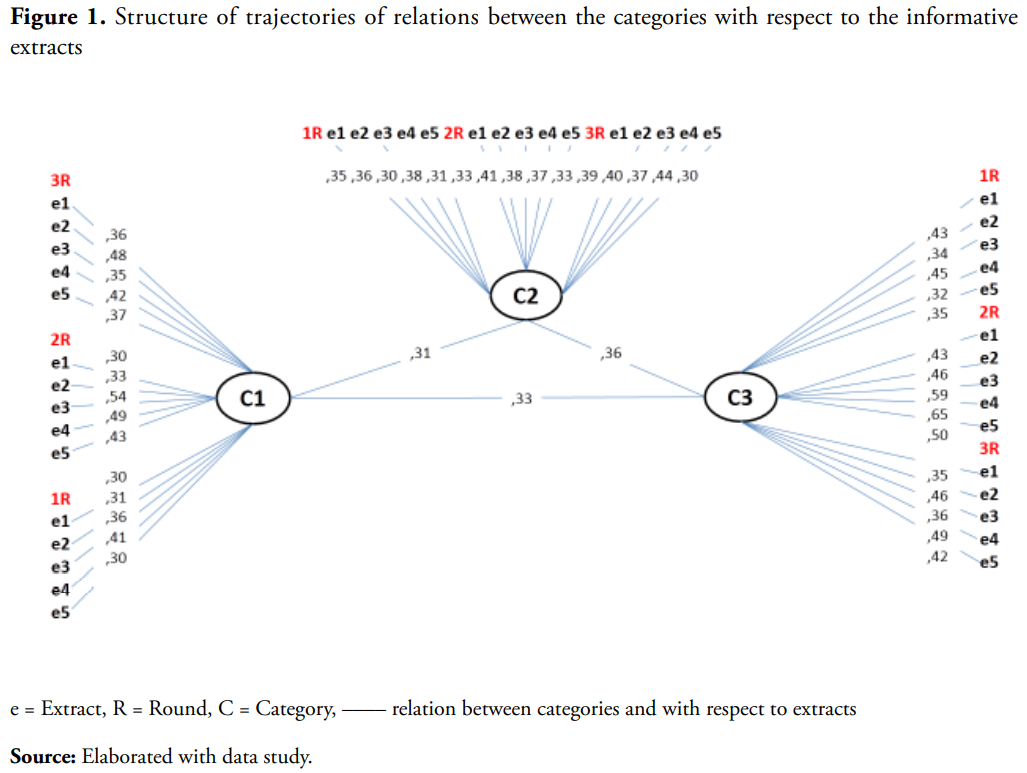

Once the significant relationships between the categories and the informative extracts qualified by the expert judges were established, we proceeded to estimate the structure of relationship trajectories (see Figure 1).

It is possible to appreciate that the structure of consensus is weak because the trajectories of relations between categories and extracts is close to zero, suggesting a spurious scenario. This indicates that the expert judges who qualified the informative extracts seem to suggest the inclusion of other variables that the revised models do not include and that refer to perceptions of risk, usefulness, efficacy and adherence to treatment.

Discussion

This work has specified a model of the determinants of adherence to treatment from the review of the MDCSS and the MDER in order to explain the follow-up of cases of accidents or diseases arising from conflicting work climates in terms of their relationships as to your tasks.

However, the model does not explain the subsequent processes of adherence to treatment, such as quality of life and subjective well-being60.

Subjective wellbeing is the result of a climate of tasks subordinated to the climate of relationships and in cases of illness or accident, adherence to treatment increased subjective well-being by empowering the employee with respect to the organization, not only the worker evaluated positively his reintegration in the company, but also contemplated other job offers with greater rewards61.

In this same sense, process of quality of life starts from the organizational culture and culminates with the reinsertion of the worker, if it circumscribes their expectations to the organizational culture62.

However, adherence to treatment is not only a mediating variable between the organizational culture and the well-being of the worker, but it also implies provisions in favor of self-care that are indicated by the frequency of medical consultations, medication intake, assistance to therapy and rehabilitation sessions63.

However, adherence to treatment is more linked to social support than to the provisions of injured or sick workers. In this phase, institutionalism determines the follow-up of cases64.

Because social security is an institutional derivative, the organizations that offer social benefits are distinguished from companies that hire their employees for periods and thus define their quality of life65.

Therefore, the relationship between adherence to treatment and quality of life would help explain the effects of the organizations’ follow-up on the cases of their injured or sick workers66.

Therefore, the specification of the model would include; 1) the organizational culture –climate, opportunities, risks, benefits, follow – ups–; 2) capacities –provisions, adhesion, skills, knowledge–; 3) biopsychosocial support –quality of treatment, family support, therapeutic assistance–; 4) quality of life and 5) subjective well-being –expectations, needs–.

Conclusion

The objective of this study was to specify a model for the study of adherence to treatment in peri-urban areas and with marginalized, excluded and vulnerable sectors such as women, children and older adults; although the research design limited the findings to the informative sample, it is suggested the extension work to repositories like Scopus and WoS.

Regarding health policies focused on adherence to treatment as a result of the formation of an intellectual capital that is guided by its self-control, it is necessary to include the State in the financing of medicines, as well as institutional and family support such as the pillars of lifestyles free of risks, health promoters and preventive of diseases and accidents.

Referencias

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. Estadísticas del SARS CoV-2 y la enfermedad Covid-19 en México. México: INEGI; 2020. https://www.inegi.org.mx/

- Bautista M, Aldana W, García C. Analysis of expectations of adherence to the treatment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) in students of a public university. Soc Per. 2018; 20(1):53-70

- Carreon J, Hernández J, Bustos JM, García C. Business promotion policies and their effects on risk perceptions in coffee growers in Xilitla, San Luis Potosí, central Mexico. Poiesis. 2017; 32:33-57.

- Carreon J. Algorithmic meta analytical of the effects of social services on the vulnerable population. J Geo Env Ear Sci Int. 2019;22(2):1-9.

- Martos M. Self-Efficacy and adherence to treatment: The mediating effects of social support. J Beh H Soc Iss, 2015; 7 (2): 19-29 https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2822/282242594002.pdf

- Carreón J. Human Development: Governance and Social Entrepre-neurship. Mexico: UNAM-ENTS; 2016.

- Carreon J. Relaciones de dependencia entre la promoción de los derechos sexuales y la economía solidaria con bajo índice de desarrollo humano. México: UNAM; 2019.

- Carreón J, Bustos J, Hernández J, Quintero M, García C. Reliability and validity of an instrument that measures attitude towards groups close to HIV / AIDS carriers. Eureka, 2020; 12(2):218-30.

- Elizarraráz G, Molina HD, Quintero ML, Sánchez R, García C. Dis- courses on organizational lucidity in strategic alliances and knowledge networks between mypimes coffee growers from central Mexico. 2018;88:1-11.

- Espinoza F, Sánchez A, García C. Knowledge management model in coffee farms in Central Mexico. Atlante Magazine: Education and Devel- opment Notebooks. 2018;6:1-13.

- Fierro E, Alvarado M, Garcia C. Contrast a model of labor commitment in a public institution of the center of Mexico. Psi. 2018;7 (13):32-48.

- Fierro E, Nava S, Garcia C. Confiabilidad y validez de un instrumento que mide el compromiso organizacional en un centro de salud comunitaria. Tlatemoani. 2018;29:42-68.

- García C, Carreón J, Bustos JM. Studies of labor migration: explor- atory factor structure of labor stigma. Eureka, 2017;14:1-16.

- García C, Carreón J, Hernández J. Limits of occupational health models. study of adherence to the treatment of asthma in elderly mi- grant workers of the State of Mexico. Management Vision. 2017;16:103-18.

- Garcia C, Martinez E, Sanchez A. Estructura factorial exploratoria de las dimensiones institucionales del compromiso laboral en una institución de educación superior (IES) del centro de México. Perspectivas. 2018;20(2):65-87. http://perspectivassociales.uanl.mx/index.php/pers/article/view/75/44

- Garcia C. Exploratory dimensions of the attitudes toward occupational health. Emp Dim. 2019;17(3):1-8.

- Garcia C. Specification a model for study of community health. Glo J Adi Reh Med. 2020;6 (5):63-7.

- Garcia C. Specification a model for study of occupational health. Glo J Man Bus Res. 2020;20(1):1-6.

- Garcia C. Specification of a self-care model. Lux. Med. 2019;42(1),15-25.

- Gratacos M, Pousa T. Intervención para mejorar la adherencia terapeútica en sujetos con esquizofrenia. Pap Psi. 2018; 39 (1): 31-44 https://www.redalyc.org/journal/778/77854690004/77854690004.pdf

- Garcia E, Gil M, Murillo M, Prats R, Vergoñás A. Community pharmacy, treatment adherence and Covid-19. Far Com. 2020; 12 (13): 51-57 https://www.farmaceuticoscomunitarios.org/en/system/files/journals/1940/articles/fc2020-12-3-05adherencia-covid19-english.pdf

- García JJ, Delgado MA, García C. Confiabilidad y validez de un instrumento que mide el bienestar sanitario. Eureka. 2018;15:1-11.

- Hernández J, Anguiano F, Valdés O, Limón GA, García C. Reliability and validity of a scale that measures professional training expectations. Margen: J Soc Work Soc Sci. 2018;89-13.

- Hernández J, Carreón J, Bustos JM, García C. Modelo de cibercultura organizacional en la innovación del conocimiento. Visión Gerencial. 2018;18:235-53.

- Hernandez J. Specification of a social intervention model against COVID-19. Bio Med J Sci Tec Res. 2020;26(3):1-4.

- Juarez M, Garcia C, Quintero M. Composición factorial confirmatoria de la norma laboral percibida. Cie Soc. 2019;1:1-14.

- Juarez M. Specification a model for study of corporate assitence. Glo J Arc Ant. 2020;11 (2):50-4.

- Limon G, Lopez S, Bustos J, Garcia C. Hybrid factors structural well-being. International Journal Psychology. 2019;1(1):1-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.35816.11524

- Llamas B, López S, García C. Specification of a model adherence to treatament. Ajayu. 2019; 17(1):140-60.

- López S, Vilchis F, Morales M, Delgado M, Olvera A, Mendoza D, García C. modelo especificado a partir de significados en torno al clima y la norma institucional en trabajadoras de un centro de salud en México. Ehq. 2019;11:11-25. http://doi.org/10.15257/ehquidad.2019.0001

- Gómez V, Llanos A. Psychosocial factors of work origin, stress and morbidity, in the world. Psychology from the Caribbean. 2014; 31:354- 85.

- Lokman S, Volker D, Zijlstra M, Brouwers E, Boon B, Beekman A, Smit F, Feltz C. Return to work intervention versus usual care for sick listed employees: Health economic investment appraisal alongside a cluster randomized trial. BMJ. 2017;7(1):1-11. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/7/10/e016348.full.pdf

- Machokoto W. A commitment under challenging circunstances: analyzing employee commitment during the fight against Covid-19 in the UK. Int J Adv Res. 2020;8(4):516-22. http://www.journalijar.com/uploads/351_IJAR-31332.pdf

- Mamani O, Apaza E, Carranza R, Rodríguez F, Mejía C. inseguridad laboral en el empleo percibida ante el impacto del COVID-19: validación de un instrumento en trabajadores peruanos (LABOR- PE-COVID-19). Rev Aso Esp Med Tra. 2020;29(3):177-256. http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/medtra/v29n3/1132-6255-medtra-29-03-184.pdf

- Mamani O, Apaza E, Carranza R, Rodríguez J, Mejía C. Inseguridad laboral en el empleo percibida ante el impacto de la Covid-19: Validación de un instrumento en trabajadores peruanos. Rev Asoc Esp Med Trab. 2020; 29(3):184-194. https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/medtra/v29n3/1132-6255-medtra-29-03-184.pdf

- Martinez E, Sánchez A, García C. Governance of quality of life and well-being subjective. Ajayu. 2019;17(1),121-39.

- Matsiu K, Yamamota K, Inoue Y. Professional commitment to ethical discussion needed from epidemiologists in the Covid-19 pandemic. J Epid. 2020; 30(9):375-6. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jea/30/9/30_JE20200278/_pdf/-char/en

- Medina L, Quintana G, Juárez I, Shafil J. Occupational to exposure Covid-19 in health care workers from latinamerican. Rev Cie Med. 2020;23(2):207-13. https://www.redalyc.org/jatsRepo/4260/426064022014/html/index.html

- Morales M, Garcia C. Exploratory factorial modelling of the sanitary habitus. Annals of Heath. 2019; 1(1):1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.10545.43365

- Ortiz M, Ortiz E. Treatment adherence in adolescents. A psicol approximation or logic or n M Mag Chi Ind. 2005;133:307-13.

- Palacios XL. Vargas adherence to chemotherapy and radiotherapy in oncology patients or logical: A REVIEW literature. Psiconcolog hy. 2011;8(2-3):423-40 http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.10545.43365

- Timm M, Soares M, Machado V. Adherence of treatment type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of randomized clinical essays. J Nur, 2013; 7 (4): 1204-1215 http://dx.doi.org/10.5205/reuol.3188-26334-1-LE.0704201318

- Hutauruc D, Wyrianto K. Effect of adherence of clinical outcomes and quality of life primary hypertension patients in pharmacy. Ind J Pha Cli Res. 2020; 3 (2): 47-33 https://talenta.usu.ac.id/index.php/idjpcr

- Park JPsychological burden and medication adherence of human of immunodeficiency virus positive patients. Health Science. 2018; 10(11):124-35. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v10n11p124

- Quintero ML, Valdés O, Delgado MA, García C. Evaluation of a model of institutional self-care strategies. Condom use and prevention in university students. Health Problem. 2018; 12(23):56-68.

- Ramirez C, García J, Garcia J. Happiness at work: Measurement scale validation. Rev Adm Emp. 2019; 59(5):327-340. https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rae/v59n5/en_0034-7590-rae-59-05-0327.pdf

- Sánchez A, Carreón J, Molina H, García C. Contrastación de un modelo de formación laboral. Int Sab. 2018;3(5):37-73.

- Sánchez A, Juárez M, Bustos JM, Fierro E, García C. Reliability and va- lidity of a knowledge management scale in a public university in central Mexico. Hispano-Am Notebooks Psychol. 2018; 17:1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.10545.43365

- Sánchez A, Juárez M, Bustos JM, García C. Contrast of a model of work expectations in ex-migrants from central Mexico. People Tech Manag. 2018;32:21-36.

- Sánchez A, Molina HD, Carreón J, García C. Hiring a Job Train- ing Model. Interconnect Knowledge. 2018; 3:37-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.10545.43365

- Sánchez R, Villegas E, Sánchez A, Espinoza F, García C. Model for the study of organizational clarity and corporate social responsibility. Model for the study of organizational lucidity and corporate social re- sponsibility. Synchrony. 2018;22:467-483.

- Sandoval FR, Villegas E, Martínez E, Hernández TJ, Quintero ML, Llamas B. Genealogy of human capital governance. Int J Eng Litera- ture Soc Sci. 2018;3:1-12.

- Silva J, Harter R, Lagervel S, Fischer F. Brazilian cross-cutural adaptation of “return to work self-efficacy” questionnaire. Rev Saude Pub. 2017; 51(8):1-9. https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rsp/v51/0034-8910-rsp-S1518-87872017051006778.pdf

- Soto A, Dorner A, García C, Hernández T. El bienestar colectivo como tema de resocialización familiar en la sociedad del capitalismo informacional. Uto. Prax. Latinoamericana. 2018;23(83):51-56.

- U Echeburr, E. Treatment adherence in intimate partner battering men in a community setting: Current reality and future challenges. Psychological Intervention. 2020; 22:87-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/ RG.2.2.10545.43365

- Urbanova, H. Competitive advantage achievement through innovation and knowledge. Journal of Competitiveness. 2013;5(1):82-96.

- Urrutia M, Gajardo M. Adherence to screening for cervical cancer Came: A view from the model of the social determinants of health. Chilean Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology y. 2015;80(2):101-10

- Verdú R, Rocha M, Almazan G. Important factors in the accession or n to treatment. A case study. Clinic and Health. 2015;26(3):141-50 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clysa.2015.07.002

- Yuan Z, Ye Z, Zhong M. Plug back into work, safety: Reattachment, leader safety commitment, and job engagement in the Covid-19 pandemic. J App Psy. 2021;106(1):62-70. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2020-87189-001.pdf

- Abdaziz M, Yossin A. Corporate innovation and organization performance: the case of Somalia telecommunication industry. Bus Eco Law Con, 2014; 4(1):260-71.

- Aghalari Z, Dahms H, Jafarian S, Gholinia and discussion of a conformist versus cooperative identity model. No- madas. 2017;50:1-18.

- Aguilar JA, Pérez MI, Pérez G, Morales ML, García C. Governance of knowledge networks: Contrasting a model for the study of consensual training. Alternativas. 2018;40:24-50.

- Amorin P, Gomes S, P Souza Almeida P, Bezerra A. No validation of a scale or of the determinants of adherence to treatment among women with breast cancer to c and cervical. Latin American Journal of Nurse y. 2015; 23(5):971-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.10545.43365

- Brouwer S, Franche R, Johson S, Lee H, Krause N, Shaw W. Return to work self-efficacy: Development and validation of a scale in claimants with musculoskeletal disorder. J Occup Rehab. 2011;21(1):244-58.

- Cardoso L, Inocenti A, Frari S, Marques B, Braga R. Grade of accession or n to psicofarmacol or logical treatment among patients discharged from the interaction or n Psychiatrist. Lat Ame J Nury. 2011;19(5):1-10

- Dantas N, Carneiro E, Santos S, Mo T, Maciqueira S, Silva K. Nursing worker Covid-19 pandemic and repercusions for workers’ mental health. Rev Gau Enf. 2021;42:1-6. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2021.20200225

- Echeburrúa E. Adherencia al tratamiento en hombres maltratadores contra la pareja en un entorno comunitario: Realidad actual y retos del futuro. Psychological Intervention. 22:87-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.10545.43365