Ciencia, Economía & Negocios, Vol. 4, No. 1, enero-junio, 2020 ISSN (Impreso): 2613-876X • ISSN (En línea): 2613-8778• Sitio web: https://revistas.intec.edu.do/

Examining the life-cycle artistic productivity of Latin american Photographers: Álvarez Bravo, Larraín, and Salgado

Examinando la productividad artística durante el ciclo de vida de Fotógrafos Latinoamericanos: Álvarez Bravo, Larraín, y Salgado

Cómo citar: ánchez-Fung, J. R. (2020). Examining the life-cycle artistic productivity of Latin american Photographers: Álvarez Bravo, Larraín, and Salgado. Ciencia, Economía y Negocios, 4(1), 85-129. Doi: https://doi.org/10.22206/ceyn.2020.v4i1.pp85-119

1. Introduction

Understanding the factors driving individuals’ productivity, including artists in various fields, is relevant from the academic and public policy perspectives, but the economics literature shows that the patterns of life-cycle artistic productivity are relatively little studied1 . Galenson and Weinberg (2000, 2001), and Galenson (2007), among others, tackle the matter head on and meet with reasonable success.

This paper seeks to contribute to the literature by examining the career output of three Latin American photographers: Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexico), Sergio Larraín (Chile), and Sebastião Salgado (Brazil). Following Galenson’s approach (2007), the research plan involves answering the question: What was each photographer’s age when producing his most influential work? Using that information, the analysis moves on to producing age-output profiles, and to establishing the conceptual or experimental nature of each photographer’s activity.

Leading contributions to the literature examine age-price profiles for painters using data from auctions and econometric modelling techniques. See, for example, Galenson and Weinberg (2000, 2001) on American and French painters, and Edwards (2004) on Latin American artists2 , but the approach is not applicable to the photographers in this paper’s sample due to the lack of auction prices, or alternative time series, for the corresponding works.

The investigation confronts the problem using alternative metrics to determine the impact of each artist’s photographs in the global scene, and subsequently associates that information with the corresponding age. In addition to contributing to the general literature on life-cycle artistic productivity, the investigation is potentially relevant for understanding the timing and nature of Latin American artists’ global contributions, and that could be valuable, for instance, in pondering decisions on public policy concerning creative industries (e.g. Peacock, 2006; UNCTAD, 2010). The subject receives little attention in the literature. In his presidential address to the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association (LACEA), Edwards (2004, page 1) argues that “Very few economists, if any, have used economic methods and data to analyze issues related to Latin American literature or arts”.

Focusing on the study’s main subjects, Manuel Álvarez Bravo is considered by many experts as the most important Latin American photographer of the 20th century. Sergio Larraín’s international career was relatively brief, but he was part of Paris-based Magnum -probably the most reputed photo agency in the world, and Salgado is without doubt amongst the most well-known photographers, Latin American or otherwise, and stills produces significant work. These statements are thoroughly corroborated by the analyses developed in this paper.

In the spirit of Galenson’s (2009) study focusing on the greatest photographers of the twentieth century, the research entails examining a range of sources to construct narratives on the Latin American photographers’ contributions. The departing point for learning about a photographer’s works and their impact rests on expert commentary in relevant academic books, but mainstream academic books are rather selective and photography receives relatively little attention vis-à-vis painting and sculpture. Encyclopaedic volumes on art history –inter alia, Kemp (2000), Davies et al’s (2011) Janson’s history of art, Foster et al (2012), and Gombrich (2016)- do not contain entries on any of the photographers selected for this study3 .

Moving on to a narrower literature, Blume (2001) comments on a series of texts about photography’s history. Her scrutiny reveals the literature’s unevenness in surveying the field, and that is to a certain extent reflected in the varying degree of treatment devoted to the photographers investigated in this project.

As an illustration, Szarkowski’s (1989) book only mentions a photograph by Álvarez Bravo, but Auer (1985) and Frizot (1998) contain entries on Álvarez Bravo and on Salgado, and the two photographers are also the subject of page-long ‘portraits’ in Marien’s (2011) classic textbook on the history of photography. More recent specialised contributions like La petite encyclopédie de la photographie (2011), Herschdorfer (2015), and Lebart (2017) include entries on Álvarez Bravo, Larraín, and Salgado.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 explains alternative measures for determining artists’ life-cycle productivity. Sections 3, 4, and 5 develop narratives on the creative lives of Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Sergio Larraín, and Sebastião Salgado, and subsequently classify each photographer as an experimental or a conceptual innovator. Section 6 examines metrics from selected museum holdings and retrospectives with the aim of gauging the narrative approach’s robustness. Section 7 concludes.

2. Identifying conceptual and experimental innovators

In a series of seminal studies on the life cycle of artistic productivity (e.g. Galenson and Weinberg, 2000, 2001; Galenson, 2007, 2009), researchers conclude that artistic innovators can be classified in two distinct categories. Conceptual innovators use artistic production in conveying ideas and emotions. This type of artist takes care to plan and implement artistic productions, and for this kind of artist the most notable contributions tend to occur at the beginning of their careers.

The other category of artists comprises what Galenson (2007) labels experimental innovators. Artists in that group progress cautiously, in a sort of learning-by-doing process, and tend to make their greatest contributions relatively late in their careers. Galenson suggests a yardstick for comparing experimental innovators and conceptual innovators: relating creation to conceptual innovators, and reproduction to experimental innovators.

Galenson and Weinberg (2000, 2001) use the approach in studying American and French painters. They employ econometric modelling in trying to formally relate an artist’s age and the market value of the corresponding work –using historical auction prices from the Guide Mayer4 .

Employing the outcome from the empirical modelling the authors derive age-price curves for various artists.

For example, Galenson and Weinberg’s research examining French painters shows Pablo Picasso’s early peak contrasting with Paul Cézanne’s late blooming. The findings lead to classifying Picasso as a conceptual innovator, and Cézanne as an experimental innovator. Galenson and Weinberg’s research agenda also investigates the careers of a range of outstanding American artists including de Koonig, Pollock, and Warhol. Edwards (2004) applies a similar approach by using auction price in estimating age-price profiles for a group of Latin American artists, inter alia, Fernando Botero and Frida Kahlo5 .

There are criticisms on, and attempts to extend, the approach using econometrics to compute age-price profiles with the subsequent objective of learning about artistic creativity patterns. See, for example, Ekelund (2002), Ginsburgh and Weyers (2006), and Ekelund et al (2015). This paper does not pursue that literature’s line of research.

Contributions to the literature employ different metrics in identifying the nature and timing of an artist’s work and impact. In fact, examining variables other than auction prices is potentially meaningful, and thus a welcome step, in trying to understand artists’ careers. Galenson and Weinberg (2000, page 773) note that,

The art market is often dismissed by scholars and critics as having little relevance to art appreciation…A salient question consequently concerns whether auction prices for contemporary art reflect sophisticated critical judgments.

In relation to this paper’s theme, Galenson (2009) focuses on determining the greatest photographers of the 20th century. He identifies Alfred Stieglitz, Walker Evans, Cindy Sherman, Man Ray, and Eugène Atget –in order of importance. Furthermore, Galenson classifies Ray and Sherman as conceptual innovators. Atget, Evans, and Stieglitz are experimental innovators. From this paper’s perspective, it is worth noting that no Latin American photographer features in Galenson’s (2009, Table 1) ranking containing 15 artists.

Employing an approach to support, or in lieu of, auction-prices-based econometric modelling, can rely on various metrics. On using art history books as a source for determining an artist’s contribution, Galenson (2007, page 36) writes:

Published surveys of art history nearly always contain photographs that reproduce the work of leading artists. These reproductions are chosen to illustrate each artist’s most important contribution or contributions. No single book can be considered definitive, because no single scholar’s judgments can be assumed to be superior to those of his peers, but pooling the evidence of the many available books can effectively provide a survey of art scholars’ opinions on what constitutes a given artist’s best period.

Notably, and of relevance for the present study, Galenson (2007) finds that results based on the prices in the auction market and textbook commentaries tend to lead to similar conclusions regarding the timing of a painter’s best work.

Retrospectives in major museums, and the resultant publications, also serve in determining the work, and time period, influencing an artist’s impact. Regarding retrospectives, Galenson (2007, page 43) notes that,

Unlike textbook illustrations, which are most often chosen to represent the author’s judgment of an artist’s most important work, systematic critical evaluations of the relative quality of artists’ work over the course of their entire careers are implicit in the composition of retrospective exhibitions.

Focusing on the potential benefits of using various metrics, Galenson (2007, page 54) asserts that,

The variety of methods by which artists’ careers can be quantified is valuable…for checking and reinforcing the validity of any single measurement. It is also valuable, however, for cases in which some sources of evidence are unavailable for an artist of interest.

Following Galenson’s (2009) approach to examining photographers’ life-cycle artistic productivity, the subsequent sections aim to build narratives on the lives and works of three outstanding Latin American photographers: Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Sergio Larraín, and Sebastião Salgado. The investigation will rely on sources with a global focus, and mainly in English. After identifying his most influential work the analysis can proceed to classifying the photographer as a conceptual or an experimental innovator.

3. Manuel Álvarez Bravo (1902-2002)

Manuel Álvarez Bravo was born on 4 February 1902 in Mexico City, Mexico. He had formal artistic education at the San Carlos Academy in Mexico, and at some point also pursued university-level studies in accounting. The German photographer Hugo Brehme, who lived and worked in Mexico for many years, was an early influence on Álvarez Bravo’s work.

His first steps in photography were motivated by interactions with the prominent American photographer Edward Weston –whose own work had modernist inclinations, and features in Galenson’s (2009) ranking among the greatest photographers of the twentieth century. The photographer Tina Modotti was an acquaintance of Álvarez Bravo, and she introduced him to Weston6 . Hopkinson (2002b) comments on the encounter:

In 1929, at Modotti’s suggestion, he sent a portfolio of images, without explanation, to the North American photographer Edward Weston. Weston replied: “I am wondering why I have been the recipient of a very fine series of photographs from you?...no matter why I have them, I must tell you how much I am enjoying them. Sincerely they are important - and if you are a new worker, photography is fortunate in having someone with your viewpoint.”

Álvarez Bravo’s international exhibition in 1935 at Julien Levy’s gallery in New York is a notable early accomplishment. His work was shown alongside two of the most influential photographers of the twentieth century: Henri Cartier-Bresson from France and Walker Evans (also prominent in Galenson’s 2019 classification) from the USA7 . The Paris-based Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation restaged the exhibition in 2004 (see Sire, 2004). The press release (see Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, 2004, page 5) remarks that Álvarez Bravo’s photos are (free translation by the author)

…representative of what would become his “surrealist” style.

A further exhibition alongside Cartier-Bresson took place in 1935 at Mexico’s Palacio de Bellas Artes. The exhibitions highlight before in some way foreshadow what is arguably Álvarez Bravo’s most influential single work: The Good Reputation Sleeping. The photograph was created following an invitation by André Breton -a central figure in the French surrealist movement. Perez (1983, page 16), at the time of writing curator of photography at the Israel Museum, writes:

…a seminal image in Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s work…conforms with the surrealist idea of automatic action and dream.

Marien (2011, page 324) adds,

“…La Buena Fama Durmiendo (Good Reputation Sleeping) (1938-39) shows a young woman slumbering in the sun…The seductive, sexually

charged nude intimates Surrealism’s concern with eroticism and altered states of consciousness; the image was shown at an exhibition organized by surrealist leader André Breton.”

Also on this photograph, Lebart (2017, page 28) comments,

...made between 1938 and 1939....one of his most important images...became emblematic of surrealist photography...

See also Kamien-Kazhdan (2007), and Manor Friedman (2008), on Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s perceived contributions to the surrealist genre. Hopkinson (2002b) notes that the photograph was not included in the cover of the art magazine Minotaure -published in Paris from 1933 to 1939, and edited by André Breton- as it was considered too risky. Regardless, the subject features in the photographer’s subsequent work. For example, the volume Collection M.+M. Auer: Une histoire de la photographie reproduces Álvarez Bravo’s photo The black cloth (page 509): it was produced in 1947 and on a theme akin to The good reputation sleeping’s. Naylor’s (1988, page 20) and Szarkowski’s (1989, page 230) texts also contain a photograph produced by Álvarez Bravo during this period –Day dreaming (1931). La petite encyclopédie de la photographie (2011) reproduces Parábola Óptica (1931), on which Hopkinson (2001, page 523) writes:

When André Breton first saw the veteran Manuel Alvarez Bravo’s image of the optician’s sign, he congratulated the Mexican people on being ‘natural surrealists’. Don Manuel could, of course, have replied with Frida Kahlo, who was paid the identical flattery: ‘Of course, I had no idea I was a Surrealist until told so by André Breton.’…‘All my work is symbols’ he uttered, and ‘my abstract photographs are precise documents.’

The most important international surrealist exhibition in Latin America was also organised by [César] Moro…In 1940 he and [Wolfgang] Contributing to our understanding of Álvarez Bravo’s standing in the international and in Mexico’s surrealist milieus, Adès (2009, pages 409-410) pens,

The most important international surrealist exhibition in Latin America was also organised by [César] Moro…In 1940 he and [Wolfgang] Paalen, with the collaboration of Breton from a distance, organized the International Exhibition of Surrealism at the Galeria de Arte Mexicano…The exhibition was intended as the latest in the series of international surrealist exhibitions that had taken place previously in Prague, London, Tenerife and Japan, as well as Paris... the most famous Mexican artist, however, Diego Rivera, together with Frida Kahlo and the photographer Manuel Alvarez Bravo, was included in the ‘surrealist artists’ section.

The relevance of Álvarez Bravo’s work among the surrealist group is without doubt the most significant indicator about the photographer’s work and its subsequent influence worldwide. Later on, critics would highlight Álvarez Bravo’s conceptual inclinations, a fitting characteristic given the association with the surrealist current. Walker (2014), page 1, states

The term “documentary” can itself be problematic in discussing Álvarez Bravo’s work. There are examples in his oeuvre where the image has been overly constructed…

Following his earlier accomplishments, Álvarez Bravo contributed to Edward Steichen’s celebrated 1955 Family of Man exhibition -originally assembled while Steichen was Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This was an outstanding recognition of Álvarez Bravo’s standing in the world of photography. Paul Strand (1968), the American who features in Galenson’s (2009) ranking of the greatest photographers of the twentieth century, writes about Álvarez Bravo,

…he has become Mexico’s greatest photographer and one of the outstanding photographers of his time.

In 1984 Álvarez Bravo won the Hasselblad Award presented by the Swedish Hasselblad Foundation. His lifetime achievements were also recognised with a retrospective exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1997, and in the same year Aperture magazine printed an issue profiling his work. The J. Paul Getty Museum celebrated the artist’s 100th birthday in 2002 with the event ‘Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Optical Parables’–the exhibition’s title alludes to the photo from 1931 mentioned elsewhere in this paper.

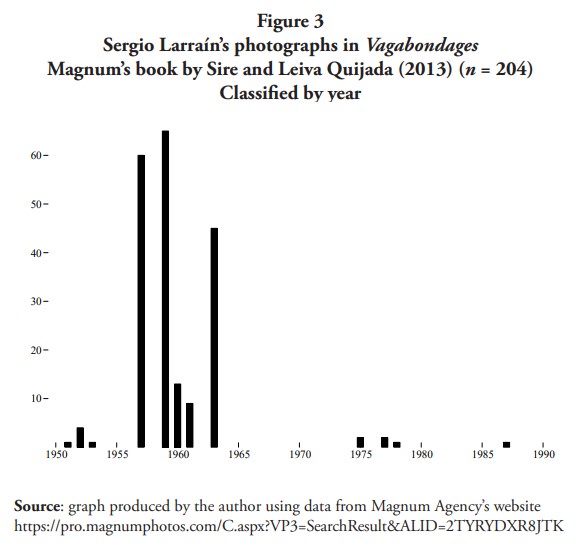

Álvarez Bravo was very influential in his native Mexico, for example, mentoring prominent photographers such as Graciela Iturbide. He died on 19 October 2002 in Mexico City. The preceding narrative points to the fact that Álvarez Bravo’s most influential contribution materialised before he was 40 years of age, and therefore leads to identifying the photographer as a ‘conceptual innovator’ (see Table 1).

4. Sergio Larraín (1931-2012)

Sergio Larraín was born on 5 November 1931 in Santiago, Chile. He had some early music education but no formal artistic training. As a young adult, he pursued university studies in California and subsequently in Michigan in the USA.

Larraín started his career in photography in 1949. His first exhibition took in 1953 in Santiago, Chile. This early stage in Larraín’s career was rather productive if measured by the fact that in 1956 New York’s Museum of Modern Art bought his photographs.

From 1958 Larraín was publishing in the Brazilian magazine O Cruzeiro. During this period, he was granted a British Council bursary to photograph London during 1958-1959. It is arguably between his time in Brazil and London that Larraín gets a major break. The opportunity arises when he meets Swiss-photographer René Burri in Río de Janeiro, and it is Burri who introduces Larraín to Henri Cartier-Bresson, whom he eventually meets in 1958. Meeting Cartier-Bresson is momentous as in 1959 the French photographer invites Larraín to join the Paris-based Magnum photo agency in 1959 –Larraín became a full member in 1961. Lebart (2017) asserts that Larraín was the first Latin American photographer to join Magnum.

But this period does not generate major developments in the photographer’s career, and Larraín actually decides to go back to his native

Chile in 1961. In a somewhat surprising move, Larraín retired from photography in 1972, and in fact was already rather inactive from 1968.

Larraín subsequently turns his focus to photography once more and produces what is likely his most significant contribution. Valparaíso was published in 1991: a collection of photographs focusing on the well-known Chilean seaside town. Magnum photo agency comments on Larraín’s work,

Sergio Larraín published only four books in his lifetime, and Valparaíso (1991) is the most impactful of them all. He began photographing the famous Chilean port in the 1950s but it was not until 1963 that he spent more time there, this time in the company of the poet Pablo Neruda. The pair explored the bohemian lifestyle of the port-side neighbourhoods, which then counted some one hundred brothels and cabarets.

Valparaíso contains text by Chilean Nobel Prize in Literature-winner Pablo Neruda. In a Financial Times article (see Willis, 2017), Larraín is labelled “the poet of Valparaiso”, declaring that “For 40 years, the reclusive photographer was obsessed with the crumbling Chilean port, drawn as much by its sordid side as its romance”. The fact that Larraín worked in an experimental fashion is further reinforced by Martin Parr, a distinguished British photographer, commenting for Magnum,

Valparaíso is great body of work, starting as a magazine assignment and turning into a full personal project. He captures an atmosphere of the city which feels both personal and heightened…

The magazine project that Martin Parr refers to was published in Du Atlantis in 1966, and the multi-stage process culminating in Valparaíso reflects an experimental approach. Magnum adds that,

Sergio Larraín may only have worked as a professional photographer for 10 years, but his signature approach – vertical frames, low angles, and an experimental approach with a humanistic documentarian’s instinct – has rendered him as an idol for photographers that followed him.

Commenting on Larraín’s celebrated photo made in Valparaíso, La petite encyclopédie de la photographie (2011, page 247) notes that (free translation by the author),

In Valparaíso…he made one of his most celebrated photos showing two girls descending via one of the steps in the port city.

On the photographer’s work style, Hopkinson (2014) writes,

Larraín was endlessly experimental. One afternoon in the 1950s, he was taking photographs outside Notre Dame in Paris and captured scenes between a couple which he only noticed when he developed the film.

Larraín’s work was exhibited in 1991 and in 2013 at the Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles, France, and in 1999 a retrospective was staged at Valencia’s Institute of Modern Art in Spain. In 2013 the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation organised an exhibition in Paris with Larraín’s photos from Santiago, London, Paris, Valparaíso, Italy, and South America; see the related publication by Sire and Leiva Quijada (2013) in collaboration with Magnum.

Sergio Larraín died on 7 February 2012 in Tulahuén, Chile. The narrative developed above points to the photographer’s most influential work originating when he was 60 years of age. The nature and timing of Larraín’s legacy mark him as an experimental innovator (see Table 1).

5. Sebastião Salgado (1944-)

Sebastião Salgado was born on 8 February 1944 in Aimorés, Brazil. He studied economics in São Paulo University and got a master’s degree in 1968. Salgado subsequently pursued postgraduate studies, also in economics, in Paris.

Salgado then worked as an economist and travelling as part of his duties prompted an interest in becoming a professional photographer. He did so from 1973 and settled in Paris, successively working for Sygma and Gamma photo agencies; and from 1979 joined the prestigious Magnum photo agency, a landmark in a budding career.

The 1980s were momentous for Salgado’s contribution to photography. During this period the photographer covered the human suffering in Mali, Chad, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Eritrea. Regarding this documentary work, Koetzle’s (2005, pages 332-337) volume incorporates icons from the period 1827-1991 and identifies Salgado’s reportage on the Sahel’s calamity as the beginning of the photographer’s subsequent global prominence.

Salgado’s documentary work placed him as a finalist in feature photography for the 1985 Pulitzer Prize “for his dramatic photos of the famine in Ethiopia”, and he won a ‘Leica Oskar Barnack Award’ in 1985 –going on to earn another in 1992, but producing the photos in the Sahel was detrimental for Salgado’s health as vividly recounted in a TED talk (see the list of URLs in the list of references). Salgado left Magnum in 1994 and established Amazonas Images in Paris.

Hiroki Ueki’s (1993) foreword on Salgado’s retrospective in The National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo (the first time the museum staged a show featuring a photographer’s work) highlights his experimental approach,

…always spends a long time to build a natural understanding with the people he is to photograph.

Hopkinson (2001, page 526) adds that,

For Sebastião…his way of working is as important as the work itself. He spends time with his subjects; he lives with them…

Related to Hopkinson’s observation, Salgado’s experimental approach in creating photo-based, humanistic, narratives, like his work on the famine in Africa’s Sahel, gets him attention in Hermange’s (1996) short essay on the history of photojournalism.

Marien’s (2011, page 426) commentary also points towards Salgado’s experimental approach to his subjects,

Salgado’s approach can be seen in his best-known series, An Uncertain Grace…The series begins with a panoramic establishing shot…The next few pictures move in closer…Later shots come in closer still… The final shot is again a wider expanse…

Salgado was also awarded the prestigious Hasselblad Award in 1989 (Álvarez Bravo got the recognition in 1984, as mentioned earlier in this paper) and a statement by the Foundation contributes to our understanding of his work’s nature and impact:

Sebastião Salgado is one of the foremost and most widely known contemporary working social documentary photojournalists. He has demonstrated a unique ability to link journalism, discrete intrusion, loyal involvement and photographic aesthetics. He uses his medium to tell the story of people’s lives, lives he observes with respect however harsh their circumstances. His pictures are moving and important to our understanding of peoples and cultures.

Salgado’s most recent project documents people and nature around the globe. Genesis, published by Taschen in 2013, is arguably his most important work, but only time will tell. Writing in The Guardian, Cumming (2013) calls him “possibly the best-loved photojournalist in the world”. La petite encyclopédie de la photographie (2011, page 148) also places Salgado amongst the most influential in his field alongside world-renowned French photographer Raymond Depardon. Cumming (2013) further comments on Genesis,

It has taken eight years, Genesis is its title, and its scope is unashamedly biblical. Salgado wants to go back to the beginning, to find a world that has not yet been ruined by mankind so that we may see the Eden that time forgot. He wants us to know the animals, plants and indigenous tribes that represent what he calls, controversially, the most pristine parts of nature.

Cumming’s commentary points towards Salgado’s experimental approach, going on to add that,

Salgado rarely goes for the decisive moment – there are comparatively few actions shot in the show, although there is a tremendous image of an anhinga bird (in water) catching a fish (leaping in the air) to turn the world upside down. His images are generally poised, polished and perfected; he works best with absolute stillness.

Wald’s (1991) commentary contributes to the impression on the nature of Salgado’s work and its impact:

In Europe, Salgado’s reputation as an outstanding photojournalist was established by a documentary project on the peasants of Latin America…and by his photographs in 1984-85 of starvation and death in the Sahel region of Africa...In the United States…his extraordinary pictures of workers at the Serra Pelada gold mine in his native Brazil…

The fact that this sort of path breaking work tends to happen when experimental artists are relatively older is in harmony with Hattenstone’s (2012) remark,

…at the age of 60, Sebastião Salgado set out on his most ambitious project... to document the world’s pristine territories – areas untainted by the brutal grind of industry, exploitation and modern life.

Reviewing Genesis, Budick (2014) asserts the experimental nature of Salgado’s lifetime work:

Sebastião Salgado approaches life encyclopaedically – not just his life, but all of it. His vision is vast, his embrace global. For his first major feat, Workers, he toured 26 countries in seven years, erecting a photographic monument to the beauty, dignity and degradation of labour. He turned next to Migrations, an exhaustive treatise on today’s wandering millions. He covered 40 nations, from the refugee

camps of Tanzania to the urban megalopolis of Latin America, and the result was a stupendous taxonomy of displacement. Exiles, refugees, seasonal labourers, guest workers and nomads of all sorts took their turn before his lens, illustrating the impact of a massive problem on individual lives. Now, Salgado has scrolled back from exodus to Genesis…

Salgado was awarded Foreign Honorary Membership of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1992, and received the Royal Photographic Society’s Centenary Medal and Honorary Fellowship in 1993. Also, as mentioned above, Salgado’s work was exhibited in a retrospective at the Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art in 1993, and since 2001 he is a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador. See Salgado (2013), pages 167-175, for an extensive list of distinctions conferred on the photographer.

Sebastião Salgado’s contributions and related age lead to classifying him as an experimental innovator. However, further metrics could help in settling whether earlier (at age 42) or subsequent (at age 69) contributions are more influential (see Table 1). That exercise will be feasible when Salgado concludes his ongoing documentary photography work.

6. Assessing museum holdings and retrospectives

As discussed before, in addition to expert commentary in art books and related publications, other sources can be valuable proxies in determining an artist’s key contributions; section 2 contains arguments concerning the potential value of inspecting retrospective exhibitions. That is particularly the case in the absence of concrete information such as that comprised in, for example, pertinent time series on auction prices. This part of the paper aims at reinforcing the narratives developed in the previous sections by deriving metrics from museum holdings and retrospective exhibitions.

On the subject of museum collections, Galenson (2007, page 48) remarks,

The decisions of museums, even apart from their assembly of retrospective exhibitions, provide another source of information on artists’ major contributions. Museums wish to present the best work of the most important artists, and they consequently reveal their judgments of what this best work is in a number of ways.

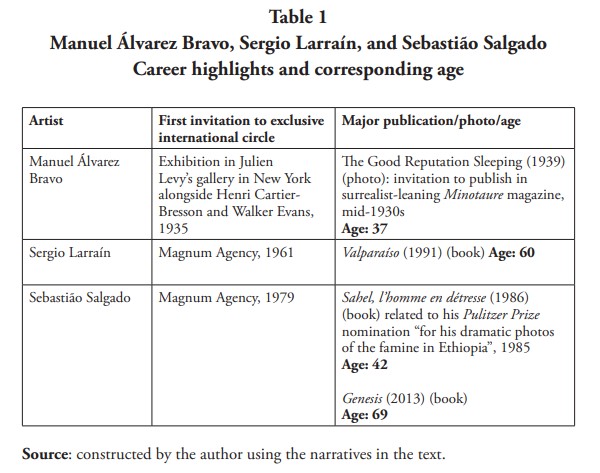

There is a unique source for throwing more light on Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s contribution: New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) holds a considerable collection of his photographs. Figure 1 shows MOMA’s holdings of Álvarez Bravo’s works: 44 photographs in total8 . The figure indicates that the collection’s vast majority of pieces are from the period comprised between 1929 and 19429 . The time span includes The Good Reputation Sleeping created in 1939 -the photographer’s frequently reproduced work. Also, as explained above, during this period Álvarez Bravo participated, alongside Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans, in a collective exhibition organised by Julien Levy in his New York Gallery

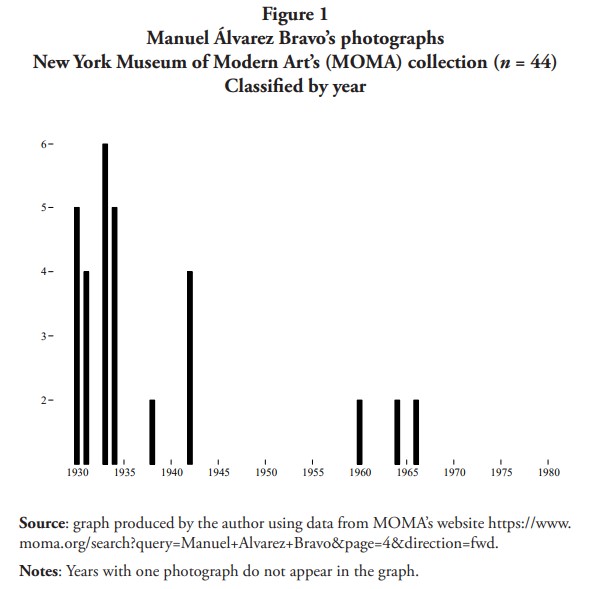

Figure 1’s data match the narrative developed in section 3: Álvarez Bravo’s photographs in MOMA’s possession are mainly from the period before he reached 40 years of age. The fact can be clearly perceived in Figure 2 displaying a cross-plot among MOMA’s holdings of Álvarez Bravo’s photographs and the corresponding age. The evidence from inspecting MOMA’s collection endorses classifying Manuel Álvarez Bravo as a conceptual innovator.

Further metrics on Álvarez Bravo’s oeuvre can be derived from the major retrospective held at Paris’ Museum of Modern Art in 1986. The exhibition included 256 black and white photographs. Almost half (126) are from the 20-year period 1920-1942, while the remaining 130 photographs cover the 40-plus-year period ranging from 1943 to 1986. Therefore, the data deriving from the retrospective held in Paris’ Museum of Modern Art corroborate the conclusions derived from Figure 2.

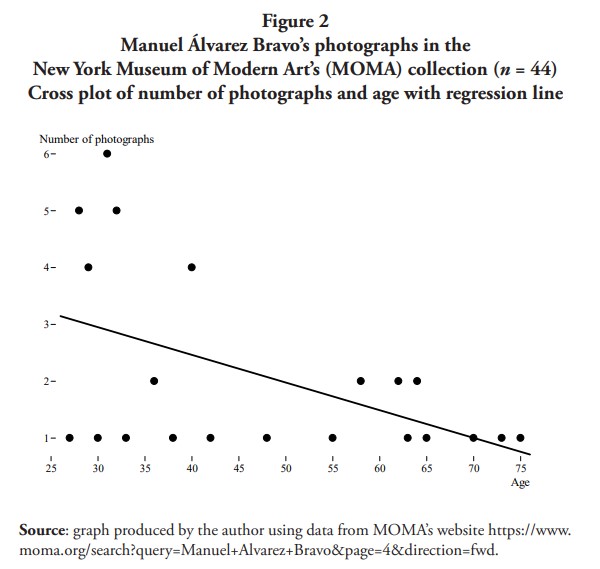

Contrasting with Álvarez Bravo’s case, MOMA only holds two photographs by Sergio Larraín: both were made in Chile, in 1952 and 1953. But there are other sources of metrics for examining the photographer’s contributions. Particularly, several retrospectives have been held to showcase Larraín’s career legacy, as noted elsewhere in the paper. One exhibition took place in Spain in 2009, and two in France in 2013 –one in Arles and another in Paris.

The exposition at the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation in Paris in 2013 is the most comprehensive. The subsequent analysis employs the corresponding printed material -supported by Magnum Agency- as a proxy for the exhibition’s portfolio of photographs. The volume includes commentaries by Sire and Leiva Quijada (2013), and contains Larraín’s photographs made in Bolivia, Peru, Argentine, London, Paris, Italy, and Valparaíso and Santiago (Chile).

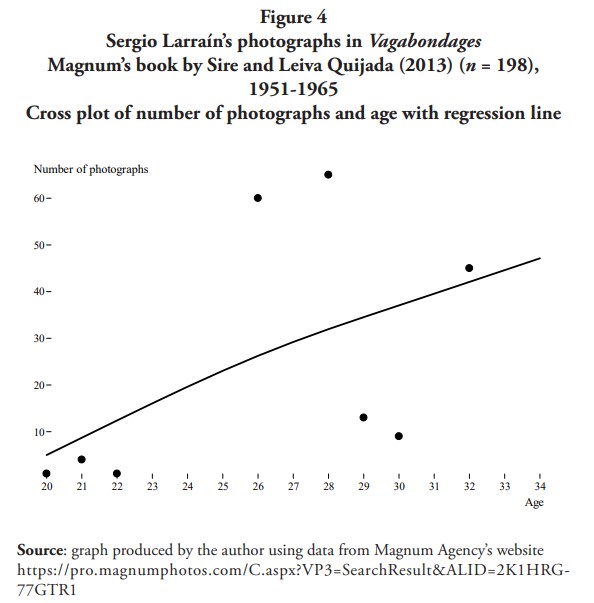

Figure 3 shows the 204 photographs by year: the vast majority correspond to the periods that Leiva Quijada labels “The first years (1954-1955)” and “The Magnum years (1959-1967)” (see Sire and Leiva Quijada, 2013). Figure 4 exhibits the age-productivity profile for Larraín revealing that the photographer’s major works belong to the period before he was 40. Sire’s (see Sire and Leiva Quijada, 2013, page 30) comments are relevant in pondering the finding (free translation by the author):

We often talk about Sergio Larraín as the “South American Robert Frank” …the two decided to stop practicing the medium at a young age to pursue other activities…

The fact entails that the narrative-based analysis in section 4 does not match the pattern arising from the retrospective at the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation in Paris. Reconciling the two sources is possible, for instance, by accommodating a story in which (even if produced at a relatively early age) Larraín’s modus operandi meant that the photographs became prominent as part of the book Valparaíso originally published in 1991 when he was 60. To this end, it is worth bearing in mind that Larraín took care to edit the book -which includes a contribution by Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet Pablo Neruda- resulting from a long-term dedication to photographing life in his native Chile. Arguably, the exhibition reflects a photographer developing solidly at a relatively early age but whose ultimate impact resides in the collection of photographs making up Valparaíso.

In that regard, probably the most popular photograph in the retrospective is that of two girls going down a flight of steps –Passage Bavestrello from 1951; see page 253 in Sire and Leiva Quijada (2013), and the photo is an integral part of the book Valparaíso. Hence it is reasonable to argue that the photo belongs in a long-term project documenting the seaside town Valparaíso, and the fact that Larraín makes the product of that endeavour public at the age of 60 reflects the photographer’s experimental approach.

An analogy would be a writer producing chapters for a book and only subsequently, years later, completing the work and getting it published –on this, see section 4 containing Martin Parr’s comment on Valparaíso’s protracted gestation process. Continuing with the analogy, any commentary about that author’s output will be attributed to the book’s publication date, regardless of how long ago parts of the tome were produced. The comparison can help in resolving the apparently incompatible conclusions deriving from the narrative in section 4 and the retrospective exhibition’s data (Figures 3 and 4).

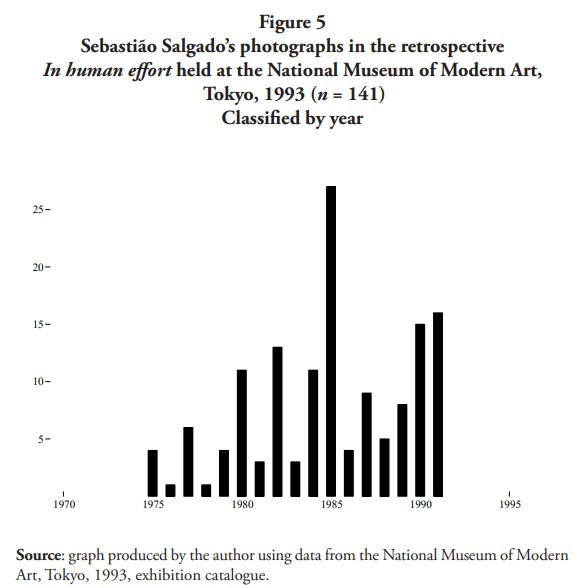

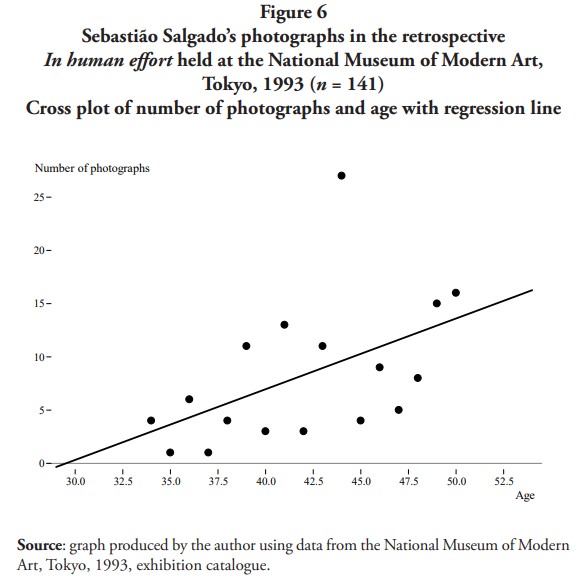

Turning to Sebastião Salgado, the analysis focuses on the major retrospective In human effort held in 1993 in Tokyo’s National Museum of Modern Art. As noted before, that was the museum’s first show by a single photographer, and therefore the retrospective is a solid point of reference for assessing Salgado’s work. The analysis employs the exposition’s printed catalogue in tallying the photographs and the corresponding years of production.

Figure 5 shows the 141 photographs in the retrospective classified by year of creation. Figure 6 exhibits a cross plot of the photographs and the corresponding age. The graph reflects the positive age-output link: the pattern confirms classifying Salgado as an experimental innovator in harmony with the narrative developed elsewhere in the paper.

As noted in section 5’s narrative, the photos from the Sahel earned Salgado a Pulitzer nomination, and the effort dedicated to producing the documentary was so morally demanding that it affected his mental and physical health, as recounted in a TED talk. Figure 5 reveals that the period contains the largest amount of photos among those included in the retrospective.

An uncertain grace is an earlier representative show (though not formally classified as a retrospective) that took place, inter alia, at the prestigious San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1990. The accompanying volume by Salgado contains a list of the photographs from the exhibition classified in four categories: Salgado, 17 times; The end of manual labor, 1986-; Diverse images, 1974-87; Famine in the Sahel, 1984-85; and Latin America, 1977-84 (see Salgado, 1990, pages 152-154). Consistent with the data obtained from the retrospective held in Tokyo (see Figure 5), 1984 onwards is the time period displaying the largest number of photographs.

Shawcross and Hodgson’s (1987, page 2) comment on Salgado’s path breaking contribution during this particular period throws further light on the photographer’s impact:

A thing of beauty is not a joy forever. That is the major problem that confronts viewers of Sebastião Salgado’s extraordinary photographs of famine in the Sahel…They were taken in…Sudan, Mali, Ethiopia- at the height of the famine of 1984-1985…Salgado presents his photographs as a documentary, almost a narrative of the catastrophe…

On the basis of the narrative in section 5 and the metrics assembled in this section, it is reasonable to argue that the photographs from the Sahel are the highlight of Salgado’s career, and were made after he was 40 years of age. For the purpose of this investigation, Salgado’s classification as an experimental innovator would not vary even if the photographer’s recent projects, particularly Genesis discussed above, go on to become rather influential, as is expected (see also Salgado, 2019).

7. Conclusion

The paper examines the creative life cycles of three Latin American photographers: Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexico), Sergio Larraín (Chile), and Sebastião Salgado (Brazil). Manuel Álvarez Bravo can be branded as a conceptual innovator, a characteristic that caught the French surrealists’ attention. On the basis of the narrative developed in the text, Álvarez Bravo’s creative peak is identified as taking place when he was 37.

In contrast, Sergio Larraín and Sebastião Salgado are classified as experimental innovators. Larraín’s career highlight is dated at the age of 60 and Salgado’s after reaching 40. The life-cycle productivity patterns identified using the narratives developed in the text are in harmony with contributions in the literature investigating the creative life cycles of conceptual and experimental innovators in various fields including painting, writing, and architecture (see Galenson, 2007).

The outcomes for Álvarez Bravo and Salgado stay robust after extracting further metrics from museum holdings and major retrospectives, but the narrative-based findings pointing to Larraín’s apparent experimental approach do not match the photographer’s classification according to the age-output profile deriving from the analysis of a major retrospective. The exposition in the main text advances arguments trying to reconcile the analyses. The impasse throws light on the pitfalls accompanying efforts to systematically determine artists’ life-cycle productivity, but overall using Galenson’s (2007) approach yields meaningful insights about the oeuvre of three of the most important Latin American photographers of the twentieth century. The results are relevant from the academic and public policy perspectives. For instance, a better understanding of life-cycle artistic productivity can inform discussions on the allocation of public funding for creative industries.

Referencias

Adès, Dawn (2009) Surrealism and its legacies in Latin America, Proceedings of the British Academy, 167, 393–422.

Ashenfelter, Orley, and Kathryn Graddy (2003) Auctions and the price of art, Journal of Economic Literature, 41, 763-787.

Aubague, Laurent (2011) Manuel Álvarez Bravo, photographe mexicain de l’abstraction figurative, Amerika, 4.

Auer, Michèle and Michel (1985) Photographers encyclopedia international 1839 to the present, Editions camera obscura, Hermance, Geneva, Switzerland.

Blume, Ana (2001) Reviewed works: Seizing the Light: A History of Photography by Robert Hirsch; An American Century of Photography by Keith F. Davis; A New History of Photography by Michel Frizot, Art on paper, volume 5, no 4, 98-99.

Bryant, William D.A., and David Throsby (2006) Creativity and the behavior of artists,

Chapter 16 in Victor A. Ginsburg and David Throsby (Editors), Handbook of the economics of art and culture, volume 1, 507-529, Elsevier, The Netherlands.

Budick, Ariella (2014) Sebastião Salgado: Genesis, ICP, New York – review, Financial Times, October 15.

Campos, Nauro F., and Renata Leite Barbosa (2009) Paintings and numbers: an econometric investigation of sales rates, prices, and returns in Latin American art auctions, Oxford Economic Papers, 61, 28-51.

Coleman, A. (1997) A little ladder, and a big one: Manuel Alvarez Bravo, MoMA, 24, 2-7.

Collection M.+M. Auer: Une histoire de la photographie (2003), Editions M.M., Hermance, Geneva, Switzerland.

Cumming, Laura (2013) Sebastião Salgado: Genesis – review, The Guardian, April 14.

Davies, Penelope J.E., Walter B. Denny, Frima Fox Hofrichter, Joseph F. Jacobs, Ana S. Roberts, and David L. Simon (2011) Janson’s history of art: The western tradition, 8th edition, Prentice Hall.

Edwards, Sebastian (2004) Presidential address: The economics of Latin American art: Creativity patterns and rates of return, Economía, 4, 1–35.

Ekelund, Robert B. (2002) Book review: David W. Galenson, Painting outside the lines: Patterns of creativity in modern art, Journal of Cultural Economics, 26, 325-327.

Ekelund, Robert B., John D. Jackson, and Robert D. Tollison (2015) Age and productivity: An empirical study of early American artists, Southern Economic Journal, 81, 1096-1116.

Foster, Hal, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, and David Joselit (2012) Art since 1900: Modernism, antimodernism, postmodernism, Thames and Hudson, London, UK.

Frizot, Michel (1998) A new history of photography, Konemann.

Galenson, David W. (2007) Old masters and young geniuses: The two life cycles of artistic creativity, Princeton University Press, USA.

Galenson, David W. (2009) The greatest photographers of the twentieth century, NBER Working Paper No. 15278, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Galenson, David W., and Bruce A. Weinberg (2000) Age and the quality of work: The case of modern American painters, Journal of Political Economy, 108, 761-777.

Galenson, David W., and Bruce A. Weinberg (2001) Creating modern art: The changing careers of painters in France from Impressionism to Cubism, American Economic Review, 91, 1063-1071.

Ginsburgh, Victor, and Sheila Weyers (2006) Creativity and life cycles of artists, Journal of Cultural Economics, 30, 91-107.

Giraud, Paul-Henri (2012) “Pruebas de lo invisible”: sur quelques photographies de Manuel Álvarez Bravo, L’Âge d’or [Online], 5.

Gombrich, Ernst H. (2016) The story of art: Luxury edition, Phaidon Press Ltd, UK.

Guiso, Luigi, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales (2006) Does culture affect economic outcomes? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 23-48.

Hattenstone, Simon (2012) Sebastião Salgado in Siberia, The Guardian, December 7.

Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation (2004) Dossier de presse: Documentary and anti-graphic photographs, reconstitution de l’exposition de 1935 à la galerie Julien Levy, New York,

Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, Paris, France.

Hermange, Emmanuel (1996) Petite histoire du photojournalisme, pages 41-40 in Une aventure contemporaine, la photographie 1955-1995: Regards sur la création photographique contemporaine. Points de vue et réflexions, Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, France.

Herschdorfer, Nathalie (Ed.) (2015) The Thames and Hudson dictionary of photography, Thames and Hudson, London

Hopkinson, Amanda (2001) Mediated worlds: Latin American photography, Bulletin of Latin American Research, 20, 520-27.

Hopkinson, Amanda (2002a) Manuel Álvarez Bravo, (Phaidon 55’s) Phaidon Press.

Hopkinson, Amanda (2002b) Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Pioneering Mexican photographer and friend of the surrealists, The Guardian, UK, October 22.

Hopkinson, Amanda (2012) Sergio Larraín obituary, The Guardian, UK, February 24.

Kamien-Kazhdan, Adina (2007) Surrealism and beyond in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel.

Kemp, Martin (2000) The Oxford history of western art, Oxford University Press, UK.

Koetzle, Hans-Michael (2005) Photo icons: Petite histoire de la photo 1827-1991, Taschen.

La petite encyclopédie de la photographie (2011) La Martinière, Paris, France.

Larraín, Sergio (with Pablo Neruda) (1991) Valparaíso, Hazam, Paris, France.

Larraín, Sergio (1998) Londres, Hazam, Paris, France.

Lebart, Luce (2017) Les grands photographes du XXe siècle, Larousse, France.

Manor Friedman, Tamar (ed.) (2008) Dreaming with open eyes: The Vera and Arturo Schwarz collection of Dada and Surrealist art in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel.

Marien, Mary Warner (2011) Photography: A cultural history, 3rd edition, Pearson.

Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (1986) Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Paris, France.

Naylo, Colin (Ed.) (1988) Contemporary photographers, second edition, St James Press, Chicago and London.

Peacock, Alan (2006) The arts and economic policy, Chapter 32 in Victor A. Ginsburg and David Throsby (Editors), Handbook of the economics of art and culture, volume 1, 1123-1140, Elsevier, The Netherlands.

Perez, Nissan N. (1983) Dreams, visions, methapors, in Dreams, visions, methapors: The photographs of Manuel Álvarez Bravo, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel.

Poniatowska, Elena (2015) El retrato del viento: Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Bulletin of Spanish Studies, 92, 1051-1062.

Salgado, Sebastião (1990) An uncertain grace: Photographs by Sebastião Salgado, Thames and Hudson, London, UK.

Salgado, Sebastião (1993) Sebastião Salgado: In human effort, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan.

Salgado, Sebastião (with Isabelle Francq) (2013) De ma terre à la terre, Presses de la Renaissance, Paris, France.

Salgado, Sebastião (2019) Gold, Taschen, Germany.

Schaffner, Ingrid, and Lisa Jacobs (Eds.) (1998) Julien Levy: Portrait of an art gallery, MIT Press, USA.

Shawcross, William, and Francis Hodgson (1987) Sebastião Salgado: Man in distress, Aperture, no 108, 2-31.

Sire, Agnès (1987) Sergio Larraín, Aperture, no 109, 28-29.

Sire, Agnès (2004) Documentary and anti-graphic photographs, Steidl.

Sire, Agnès, and Gonzalo Leiva Quijada (2013) Sergio Larraín: Vagabondages, Éditions Xavier Barral.

Strand, Paul (1968) Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Aperture, no 4, 2-9.

Szarkowski, John (1989) Photography until now, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA.

Ueki, Hiroshi (1993) Foreword in Sebastião Salgado: In human effort, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Japan.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2010) Creative economy: A feasible development option, Geneva, Switzerland.

Wald, Matthew L. (1991) Sebastião Salgado: The eye of the photojournalist, The New York Times Magazine, June 9.

Walker, Ian (2014) Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Surrealism and documentary photography, Journal of Surrealism and the Americas, 1-27.

Willis, Simon (2017) Sergio Larraín: the poet of Valparaíso, Financial Times, January 20.

URLs

Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s Hasselblad Foundation award 1984: http://www.hasselbladfoundation.org/wp/manuel-alvarez-bravo/

Magnum photo agency on Sergio Larraín’s Valparaíso: https://www.magnumphotos.com/arts-culture/society-arts-culture/sergio-larrain-valparaiso/

Sergio Larraín’s exhibition in the Valencia Institute of Modern Art, Spain: https://www.ivam.es/en/exposiciones/sergio-larrain/

Sebastião Salgado’s agency Amazonas Images: https://www.amazonasimages.com/sebastiao-salgado Sebastião Salgado’s Hasselblad Foundation award 1989: http://www.hasselbladfoundation.org/wp/sebastiao-salgado-2/

Sebastião Salgado’s TED talk: The silent drama of photography: https://www.ted.com/talks/sebastiao_salgado_the_silent_drama_of_ photography